Neoplatonism, Gnosticism, Hermeticism, Esotericism, Occultism, Mysticism, Kabbalism, Spiritualism, Theosophy, & Metaphysics

With the specialization of knowledge that has occurred post-enlightenment, many disciplines have developed their own vocabularies. Before would-be students can make progress learning the logic of an area of study, they must become accustomed to the grammar. In terms of some of the topics that are within the purview of this channel, that includes gaining familiarity with words such as “esoteric,” “gnostic,” “hermetic,” “mystic,” “neoplatonic,” “occultic,” and much else besides.

These words often lie outside the scope of what one encounters in a largely secularized primary and secondary public education. And yet they are used liberally – both individually and in combination – in explorations of alternative spirituality, whether one is interested in the contemporary scene or in its history.

So, since knowledge is power, in this presentation, I am going to tackle, and try to clarify and distinguish, ten (10) words. The list is, to an extent, personal. These terms were some of those that gave me trouble in my own reading. Therefore, this list is the one that I wish I had found myself earlier in my investigations.

In-depth treatments of each of these ten words – or, more accurately, the ideas they name – will be the subject of follow-up videos. For the time being, and in order to ensure that this isn’t 10 hours long, I will merely provide sketches.

The hope is that, with even limited outlines, the distinct definitions of these words – and, by extension, the identifying concepts – will come into view giving hearers or readers a handle with which to grab hold of more detail later on.

That said, here are my list of 10 Arcane Words That Are Frequently Confused.

- Neoplatonism

Like many of the words on this list, “Neoplatonism” actually refers to a family of related views, rather than to a single outlook. I already have pages of notes tracing this more fully. But for present purposes, I want to suggest that Neoplatonism is, first and foremost, a philosophy.

To be sure, it has religious overtones and implications for theology (that is, the study of God). And those who adopt a thoroughgoing Neoplatonic perspective are frequently inclined – whether antecedently or consequently! – towards mysticism (which word we will look at in a few minutes).

But, Neoplatonism arose out of the thought and writing of Plato, who was one of the most famous philosophers to have ever lived.

Moreover, Plato founded a school, called the “Academy,” dedicated to the study of philosophy.

The primary originators and early expositors of Neoplatonism, chiefly Plotinus, Porphyry, Iamblichus, and Proclus, are – present YouTube video notwithstanding – more likely to be mentioned in philosophy classes than in any other context.

The most prominent philosophical writing in this category is known as the Enneads (a word that, in Greek, means “the nines,” and refers to the fact that the document, based on Plotinus’s thought – as edited and arranged by Porphyry – is comprised of six groups of nine treatises.

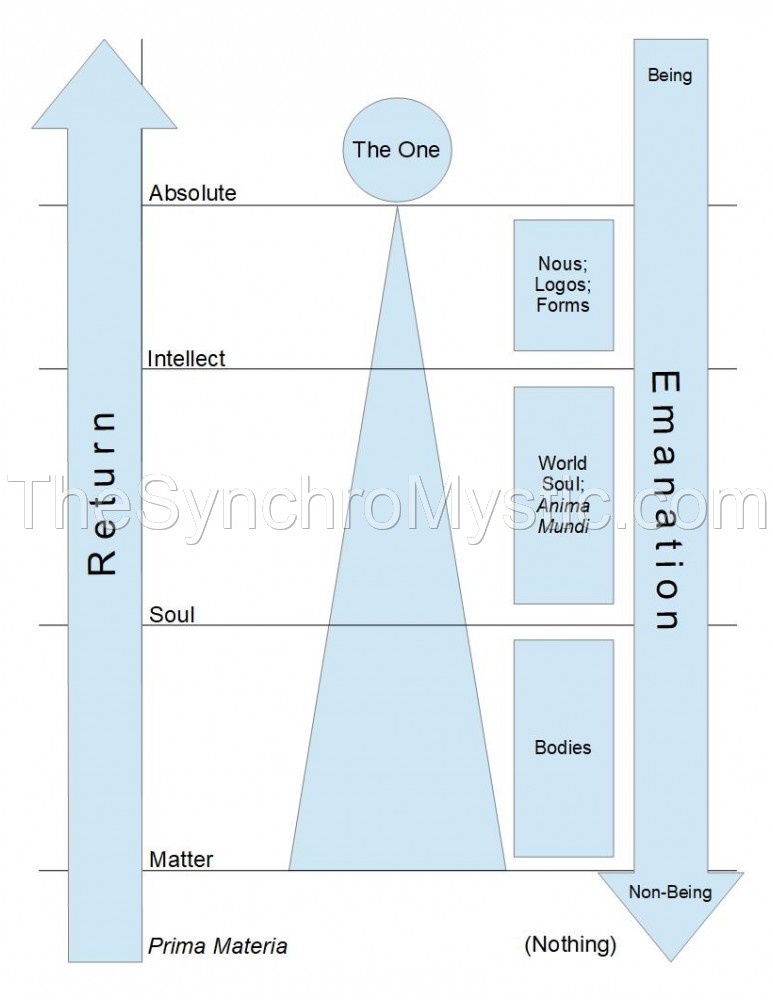

An important, distinguishing feature of Neoplatonic thought is that reality – that is, absolutely everything, from Being all the way down to non-being – is situated along a sort of hierarchy. At the very top of this “chain of being” is the One, about which we can know and say virtually nothing.

However, the One emanates or radiates being in such a way as to create three lower realms of intellect, soul, and matter. For this reason, Neoplatonism is sometimes regarded as veering close to pantheism (or the idea that literally all that exists just is part of god) or the related idea of panentheism (which may be crudely thought of as the belief that the universe is something like God’s body but that God’s mind goes beyond, or transcends, the universe).

In any case, these lower worlds – and their occupants – are deficient, both ethically and ontologically (that is, in terms of their measure of existence). So, the sensitive Neoplatonist will desire to “return to the One” via a process of “ascending” up through the higher spheres on the hierarchy.

Neoplatonism had a profound impact both on traditional and alternative religion. Arguably, the Latin Catholic Church Father St. Augustine had a significant Platonic – and Neoplatonic – orientation.

Similarly, Christians – notably Michael Psellos – in the Byzantine Empire formed a belt of transmission for Neoplatonism into the high Middle Ages.

Around the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, Neoplatonism was communicated to the west by Greek emissaries and expatriates such as Gemistos Pletho and Cardinal Bessarion.

Although traces of this Neoplatonic current are detectable in such people as the German-born Nicholas of Cusa, an especial concentration arose in Italy. Among these important Italians were those, like Marsilio Ficino and Pico Della Mirandola, who were in Florence. Later, this included people a little further afield, such as the Venetian Franciscus Patricius.

There was a curious intellectual pipeline between Italy and England where, in the 17th century, a loose confederation of diverse thinkers would develop a version of Platonism associated particularly with Cambridge University. These thinkers, including principally Ralph Cudworth, Henry More, and Benjamin Whichcote, bucked the “blank slate” empiricism of John Locke (and others) by developing a version of innate ideas that would influence linguist Noam Chomsky some three hundred years later.

Furthermore, Neoplatonic influences are detectable in the thinking of Hermetic philosopher Giordano Bruno as well as in the speculations of Swedish polymath and mystic Emanuel Swedenborg.

- Gnosticism

As a term, “Gnosticism” was coined by the Cambridge-Platonist scholar Henry More.

As a system, Gnosticism, by contrast, and despite numerous similarities with Neoplatonism, is perhaps best characterized as a theology. To be precise, it’s an often dizzying array of competing theologies.

Of course, Gnostic thought can be analyzed and explicated philosophically.

But many of the primary exponents of Gnosticism were either regarded (in their own times, or now) as theologians or they were encountered in religious contexts.

For example, Simon Magus, sometimes described as the “founder of Gnosticism,” was himself a biblical figure. You can read about him, and his confrontation with Jesus’s apostle Peter, in the eighth chapter of the fifth book of the New Testament, titled the “Acts of the Apostles.”

Or again, Valentinus, an important second-century gnostic who lent his name to a system known as Valentianism, was a theologian who may at one time have even been a candidate for the rôle of bishop in the nascent establishment-Christian church.

Much the same description could be given of other relevant personalities, such as Basilides, Marcion, and the later, Persian prophet Mani.

Writings representative of Gnosticism include an array of ancient books, collectively termed the “Gnostic Gospels,” that includes the Gospel of Philip, the Gospel of Seth, and the Gospel of Truth.

Due to the heavy, albeit heterodox, Christian flavor of Gnosticism, it is often called a Christian heresy.

Like Neoplatonism, many forms of Gnosticism described reality as a series of overlapping spheres. And gnostics often advanced a version of the doctrine of emanation.

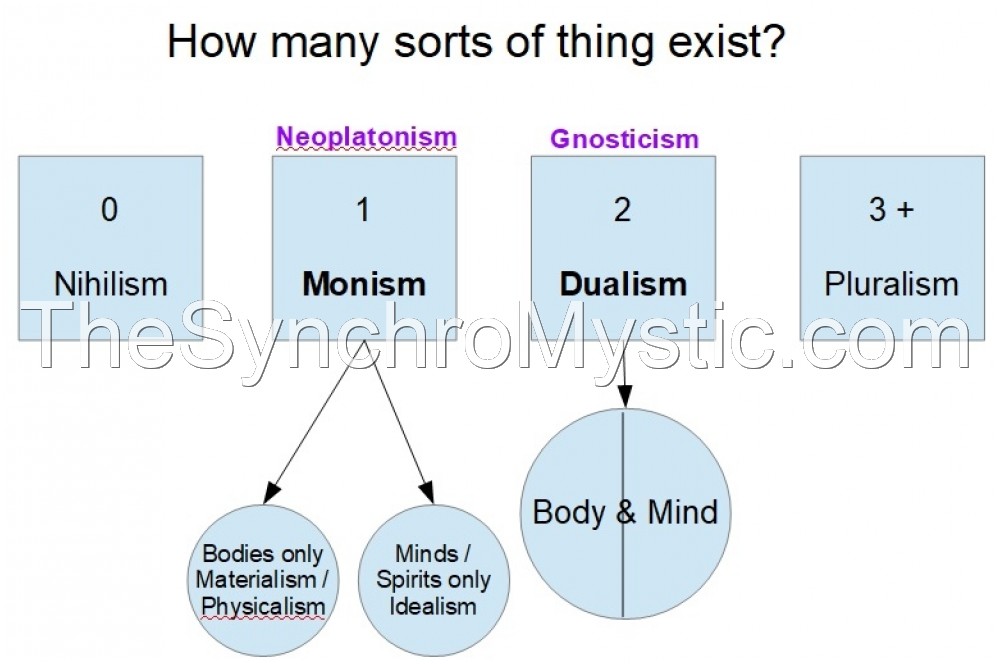

But unlike Neoplatonism, which tends to be very monistic – that is, it holds that all existing things are somehow emanations of the One – Gnosticism is explicitly dualistic.

To put it another way, gnostics held that reality was composed of two irreducible components: matter and spirit. Matter is the province of evil; spirit is associated with, and strives, for the good.

The problem is that humans (or, at least, some humans) are spirits trapped in bodily, material form.

This situation – of celestial souls unnaturally relegated to the mundane world – was frequently blamed on an entity, sometimes associated with Plato’s “Demiurge,” which had creative powers but a foolish, imperfect, or even malevolent disposition.

This character was sometimes further identified with the God of the Old Testament – or the “Hebrew Bible” – as, for example in Marcionism.

For elect humans, the path of freedom and redemption is to free these imprisoned “divine sparks” from matter. This process can only begin when a person acquires this hidden information about humanity’s true nature. This knowledge is what is meant by the word “gnosis” – which is a bit like the Eastern religious notion of “Enlightenment.”

Gnosticism crops up repeatedly in studies of those movements that were deemed heretical by the medieval church: Priscillianism, Paulicianism, Bogomilism, Catharism, and so on, all are usually classified as species of Gnosticism.

Additionally, the theological speculations of the offbeat early modern mystic Jakob Boehme are sometimes characterized as Gnostic-like. And Gnosticism is sometimes said to be the inspiration for the cryptic letter “G” that frequently appears inside the Freemasonic compass-and-square emblem.

A major restatement or revival of Gnosticism occurred within the Theosophical Society, founded in 1875 by H. P. Blavatsky, Henry Steel Olcott, William Quan Judge, and others. This organzation, in turn, influenced the creation of several Gnostic offshoots, including G. R. S. Mead’s Quest Society as well as the “Ariosophy” of Austrian occultists Guido von List and Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels.

The 19th-century “Occult Revival” – which we will continually remark upon – also gave rise (in part) to manifestly Gnostic-themed institutions such as the “Gnostic Church” (i.e., the Église Gnostique), the creation of which is attributed to Jules Doinel, and which would later be linked to the Ordo Templi Orientis and occultist Aleister Crowley.

It also shows up as a thread in the Process Theology of Hans Jonas, which was also inspired by the Process Philosophy of British mathematician and theorist Alfred North Whitehead.

- Hermeticism

Both Gnosticism and Neoplatonism seem to have arisen in the Greco-Roman world. Though, Gnosticism may have had some Jewish antecedents.

In general, these systems were part of a proliferation of worldviews that characterized the Hellenistic and early Roman periods. Part of the reason for this intellectual and spiritual volatility was the introduction of foreign ideas into Greek thought.

Due to increased trade and imperial expansion, Greeks came into contact with “oriental” philosophical concepts as well as with the mythologies and religions of other major people groups. At the time, this certainly would have included beliefs and practices from Egypt and Persia – but possibly also India.

Our third difficult word, “Hermeticism,” designates an additional set of ideas that likewise originated during this tumultuous interval, and that also represented a blending of Egyptian and Greco-Roman myth.

The fountainhead of Hermeticism was the legendary Hermes Trismegistus.

Hermes Trismegistus was, in the first place, a composite of the Egyptian gods Tahuti or Thoth and Hermes-Mercury from Classical mythology.

However, later hermeticists would further link this fabled character with the Hebrew patriarch Enoch and the Islamic prophet Idris.

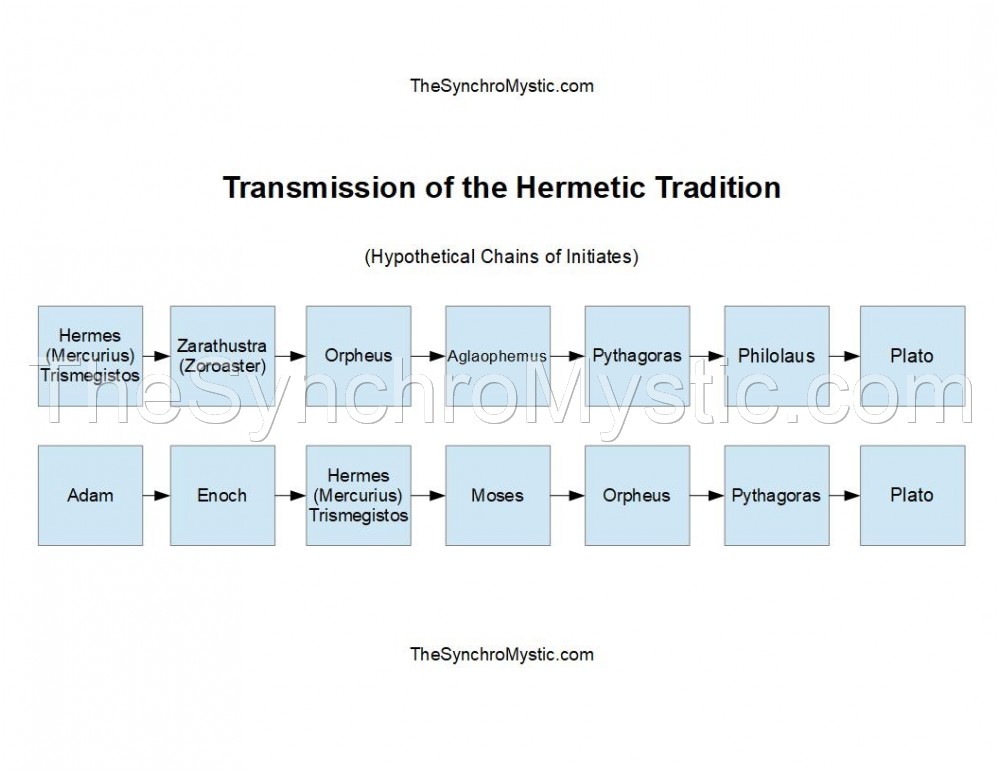

Sometimes, these figures are conflated or identified; while, other times, they are imagined to stand in a great sequence of initiates passing down a wisdom tradition. In this latter case, Hermes was seen as a teacher who conveyed his secret teachings to various philosophers and sages, including Orpheus, Pythagoras (to whom I dedicated an entire video), and even Plato.

The name Hermes Trismegistus means “Thrice-Great Hermes,” or “Hermes Who Is Three-Times Great.” The reference, here, is understood to be Hermes’ mastery of the three subjects that were variously called the “Hermetic Arts” or the “Hermetic Sciences”: alchemy, astrology, and magic.

The thing to notice, I think, is that these disciplines are, in the first place, very practical – meaning that they are bound up with practices, as opposed to just armchair speculation about the universe.

For example, alchemy deals in chemical formulas and the manipulation of physical substances. Astrology depends upon calculations of planet and star positions that, in the ancient world, would have been made by hand. And magic, also called “theurgy,” frequently employs material objects and elaborate rituals and spells. A magician actually has to do or say certain things in order to effect results.

All these aspects of Hermeticism, arguably, held the promise of empowering practitioners to influence the world and people around them. In other words, they were practiced to bring about tangible results and not simply to gain knowledge for its own sake or even for individual illumination.

Therefore, Hermeticism is intensely – and, I’ll even say, primarily – practical. Whereas both Gnosticism and Neoplatonism are, to a large extent anyway, theoretical.

That said, various individuals may have had both practical and theoretical interests.

For instance, you find that the Neo-Pythagorean philosopher Apollonius of Tyana was said to have been a “wonder-worker” in addition to a philosopher. He was (so to speak) both a doer and a thinker.

And this combination of theory and practice also characterizes certain kinds of Neoplatonism, such as the theurgy-infused variety that started with Iamblichus.

Similarly, it is conceivable that certain forms of Gnosticism also crisscrossed with Hermeticism.

For example, the 3rd to 4th-c. figure Zosimos of Panopolis was known as both an alchemist and a gnostic. Additionally, the rich cache of documents discovered at Nag Hammadi in Egypt reveal Gnostic Gospels preserved side by side with the Asclepius, a key treatise in the Corpus Hermeticum.

It appears that Hermetic thinking and the Hermetica had a wide appeal. This is possibly due (at least partly) to the fact that, in an of itself, the lore surrounding Hermes Trismegistus is far less of a complete worldview than the other two systems previously surveyed. It’s more of a collection of stories.

I’m inclined to think that, when dedicated theorists assimilated Hermetic ideas, the overall framework could either end up as a species of Gnosticism or, more likely, a kind of Neoplatonism.

I say “more likely a kind of Neoplatonism” simply because many Hermetic practices – like the fabled goal of turning lead into gold – required interaction with matter in ways that might not have sat well with a thoroughgoing Gnostic. Recall, after all, that – generally speaking – Gnostics had an aversion towards (or even totally rejected) the material world.

Nevertheless, let’s say it this way. Hermeticism can be seen as a cluster of exercises that could appeal to more practically minded people who have no theoretical aspirations or commitments to speak of.

But …Hermetic practices could also be explained in terms of, and integrated into, more sophisticated philosophical or theological systems – such as those built by Gnostics or Neoplatonists.

Hermeticism was a feature of the thinking of Renaissance figures such as the previously mentioned Marsilio Ficino, as well as of Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, Francesco Giorgi, and Paracelsus.

It was explicitly incorporated into the 17th– c. Rosicrucian movement by its mysterious apologists, including – in the category of possible authors – the German Protestants Johann Valentin Andreae, Christopher Besoldus, and Tobias Hess; and – in the category of sympathizers – the English Paracelsian doctor Robert Fludd and the Lutheran alchemists Heinrich Khunrath and Michael Maier.

These figures exercised a seminal influence on people such as the English antiquarian Elias Ashmole, who seems to have helped pass the torch of Hermeticism onto what, in the eighteenth century, would develop into Freemasonry.

Finally, several 19th-c. Masons would go on to found Hermetic-infused orders during the 19th and 20th centuries. Various incarnations of these Rosicrucian Societies (or Societas Rosicruciana) were established in England, Scotland, and the United States. And we cannot neglect to mention the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, organized by William Robert Woodman, William Wynn Westcott, and Samuel Liddell “MacGregor” Mathers.

Apparently along a somewhat separate trajectory, 19th-c. reputed sex magician and alchemist Paschal Beverly Randolph started his own Rosicrucian Fraternity in the 1850s. And then, in the 20th century, H. Spencer Lewis launched the Ancient Mystical Order Rosae Crucis, while Max Heindel would go on to found the Rosicrucian Fellowship.

- Esotericism

Recall that Hermeticism was centrally concerned with various applied disciplines. But, saying that Hermeticism is mainly practical by no means implies that it had no theoretical aspects at all.

To put it roughly, in order for hermetic practices to be justified – to say nothing about their being likely to effect results – certain things would have to be true of the world. Codifying and stating these prerequisites is the purview of theoreticians.

For instance, making no claims about the truth of the discipline, it’s clear that an astrologer wouldn’t be able to analyze someone’s personality, or predict her failures and successes – even in principle – unless the stars were somehow correlated with the subject’s life. Thus, astrology requires that a correspondence exist between the celestial world and the everyday world of human experience.

When one attempts to spell out these preconditions, one discovers that Hermeticism shares a few cosmological or metaphysical ideas with Gnosticism, Neoplatonism, and derivative systems.

We can speak about some of these essential features in the abstract – without getting bogged down with the details of any particular system. To do so, it is helpful to have a word handy. And one name that is routinely applied to these underlying – or overarching – commonalities is “Esotericism.”

So… what are some of these general qualities that are observed across a wide variety of philosophical-religious systems, including Neoplatonism, Gnosticism, and Hermeticism?

According to the late British historian Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, following French scholar Antoine Faivre, there are several hallmarks of Esotericism. I have my own list of ten that I plan to present in a separate video. But, for now, I’ll list two.

Firstly, we have the existence of Correspondences.

This is perhaps clearest in Hermeticism, where symbolical connexions between the cosmos and human beings are referred to by the dictum “as above, so below.” However, even in Gnosticism and Neoplatonism there are associations and “sympathies” between “lower realities” (such as the embodied soul) – these lower realities are called the “microcosm” – and “higher realities” (such as the Pleroma and the world soul) that are a part of the “macrocosm.”

Secondly, there is the related idea that a chain or hierarchy of being connects the microcosm and macrocosm. Goodrick-Clarke calls this intermediary realm the “mesocosm.”

Whatever it is called, and however it’s explained, it lies beneath certain theoretical notions – such as the ideas of emanation and the ascent of the soul that, in different ways, are expressed in both Gnosticism and Neoplatonism. But, it also motivates some of the practices of Hermeticism.

For example, consider that alchemical transmutation – whether of base metals into gold or of human souls into more enlightened entities – only makes sense in a system where lower realities are somehow connected to, and can access, or be transformed into, higher realities.

There’s one additional feature that we should mention. It has to do with the meaning of the word “esoteric” itself. Etymologically, the prefix “eso-” has to do with something that is “inside.”

From the standpoint of a given wisdom school, what’s in view is an “inner tradition” that one must be initiated into in order to go from being an outsider to becoming a member of the inner circle.

Let’s do a quick review.

Gnosticism and Neoplatonism are both theoretical systems (the former leaning more toward theology and the latter more toward philosophy). Hermeticism, on the other hand, is a cluster of practical disciplines. The Hermeticist need not be overly concerned with theories at all.

But, if he or she is somewhat theoretically inclined, the Hermetic arts could be combined with one theory or other. And, indeed, we named people who – historically – were taken to have combined Hermetic practices with either Gnosticism or Neoplatonism.

Nevertheless, at a high level of abstraction, Gnosticism, Neoplatonism, and Hermeticism arguably have a few things in common – not least that they represent bodies of teaching that, in some sense, one has to be initiated into. And these similarities, considered generally, might be called Esotericism.

But, these words – Neoplatonism, Gnosticism, Hermeticism, and Esotericism – are far from the only ones that might be encountered – or that may confound.

- Occultism

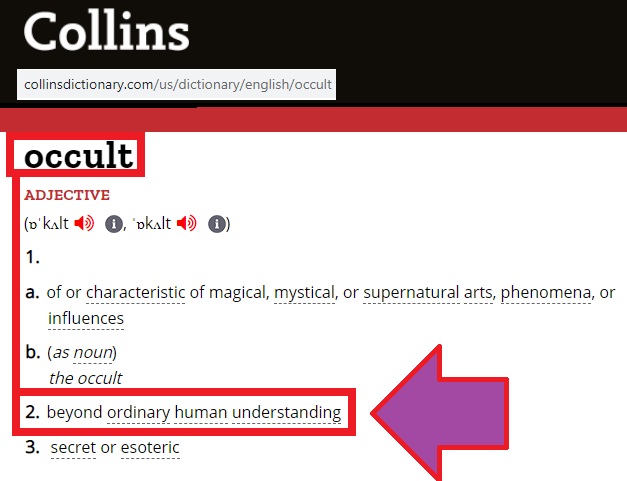

We should also consider the related word “Occultism.”

Denotatively, the word “occult” means concealed or hidden. It carries the sense of something transmitted or held in secret.

It’s arguable, therefore, that the words “occult” and “esoteric” are close cousins – even interchangeable.

Moreover, connotatively, “occult” is sometimes made to refer to that which is forbidden. In this way, something “occultic” is concealed or obscured in virtue of its being on the “dark side” of things.

Relatedly, it’s sometimes used as a way of labeling some belief or practice “irrational.”

To confuse things further, there was a tradition of using the phrase “occult sciences” to designate those Hermetic arts – alchemy, astrology, and magic – that constitute the “three parts of the wisdom of the whole universe,” according to the enigmatic alchemical text known as the Emerald Tablet.

Therefore, it is possible to employ “occultism” as a synonym for Hermeticism.

Keep in mind that our modern word “science” comes from the Latin scientia, which simply meant “knowledge.”

One cannot forgot, also, that the late-15th-early-16th-c. natural magician and scholar Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa wrote a book, published circa 1531, literally titled “Occult Philosophy” (De Occulta Philosophia). These, and other related, used show that the word certainly has a long pedigree.

But, the current academic usage of “occultism” is different than any of these. It is standard to use the word “occultism” as a technical term for the often bewildering varieties of Esotericism that emerged in the 19th century, first in France and then in America and Europe more broadly.

One crucial early figure in this so-called “Occult Revival,” is Alphonse Louis Constant, better known as Éliphas Lévi – whom we highlighted in a recent “Top 10” video.

In his 1856 book, Dogma and Ritual of High Magic, Lévi used the word “occult” (or one of its cognates) dozens of times. Some of the most oft-used and pervasive references, at least in Arthur Edward Waite’s English translation, talk of “occult philosophy” and “occult understanding” as well as something that Lévi deems “occult science.”

In his native France, Lévi influenced Gérard Encausse, also more commonly referred to by his assumed name, “Papus.” Papus was the founder of contemporary Martinism, a movement named after, and inspired by, the obscure 18th-c. magician, Martinez de Pasqually.

Lévi’s vocabulary and thinking was also transmitted into Anglo-American circles, for example, via the aforementioned A. E. Waite but also through British orientalist Kenneth R. H. Mackenzie and, later, the previous named American Rosicrucian writer H. Spencer Lewis.

Thus, similarly to Hermeticism, “occultism” has come to be partially associated with esoteric or “high-grade” Freemasonry, 19th-c. Rosicrucianism, and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.

But, things once again get confusing, not least because several of these occult currents – chiefly Freemasonry and Rosicrucianism – had earlier manifestations in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Another confusion arises from the historical fact that this occult revival also affected a broader assortment of people than members of fraternal organizations and would-be ceremonial magicians.

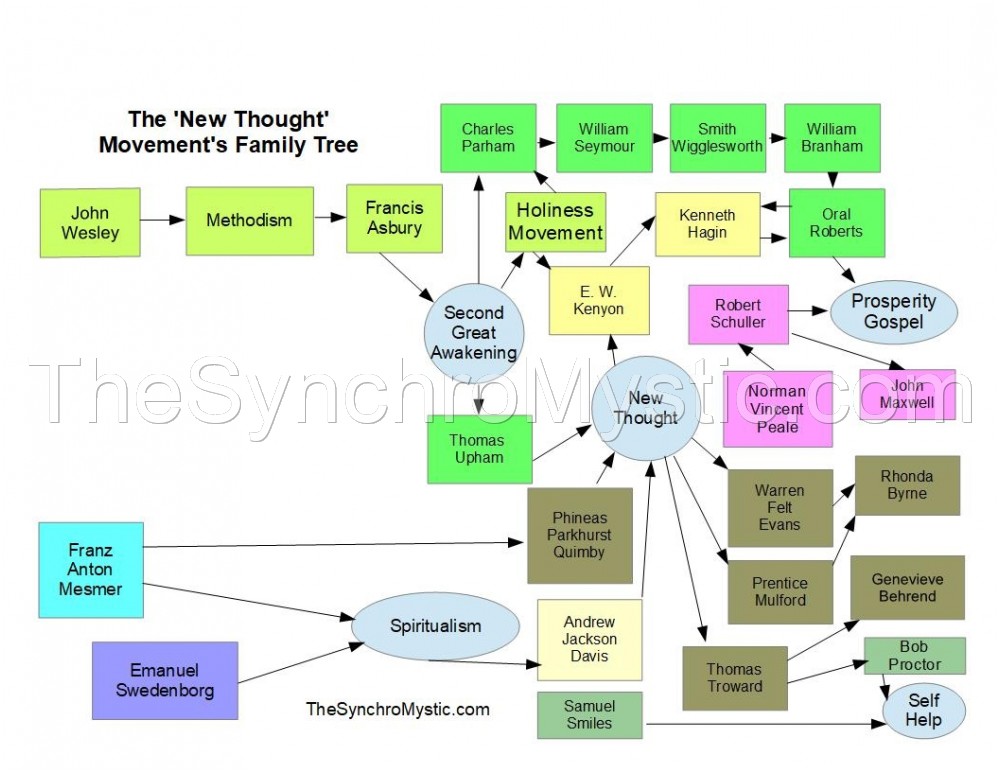

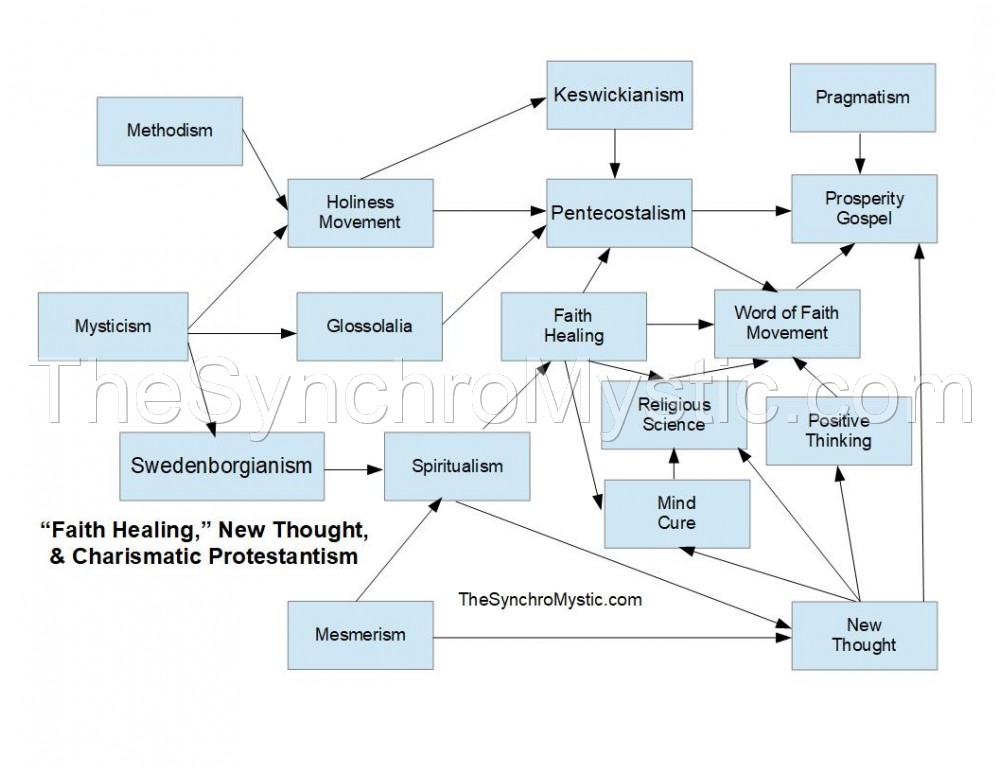

The phrase “occult revival” is also applied to Anglo-American Mesmermism and various students of the “paranormal,” as those coalesced, for example, in movements like “New Thought,” “Religious Science,” Spiritualism (about which we will have more to say in a moment), and the allied “Spiritism.”

We shouldn’t neglect to remark upon the growing pan-religious attitudes, seeds of which were fertilized during the Second Great Awakening, and which would be on display in the World Parliament of Religions at the World’s Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago, Illinois in 1893.

This was he atmosphere in which H. P. Blavatsky’s Theosophical Society would blossom and grow into a worldwide phenomenon, seeking to fuse Eastern and Western forms of Esotericism.

- Mysticism

Source: By © Raimond Spekking, CC BY-SA 4.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=33394331

By this point, I’m sure it won’t surprise viewers to learn that the word “Mysticism” – which surfaced in conjunction with several systems of thought (for example, Neoplatonism) and multiple individuals (like Jakob Boehme) previously mentioned – has its own assortment of meanings.

On the pejorative end of the spectrum, it is sometimes used as a term of disparagement for those ways of thinking – including some just surveyed – that are perceived by critics to be somehow insufficiently based on or concerned with evidence and reason. In this vein, and similarly to one of the popular-level definitions for “occult,” “mystical” becomes synonymous with words such as “irrational” and is often contrasted with (something like) “scientific.”

But, “Mysticism” is also a technical term in theology. In that field of study, it has to do with a kind of religious experience that is usually glossed as being a direct encounter with the divine.

Like Hermeticism, which picked out a trio of hands-on esoteric exercises or occult operations, Mysticism is also essentially practical.

The mystic is a person who does something. She wants to have the mystical experience.

Things complicate at two – interrelated – levels (at least).

Firstly, there may be wide – and possibly system-dependent – disagreement about the methods available to the mystic. This can be seen by contrasting the Neoplatonists Plotinus and Iamblichus.

Arguably, both thinkers were philosophers who were concerned not only with talking about reunion with the One, but about achieving it as well. Nevertheless, at its most basic, we might say that Plotinus’s approach was thoroughly contemplative, whereas Iamblichus’s was partially magical.

The point is that within broadly the same system – in this example, Neoplatonism – two figures recommended different mystical methods.

But, secondly, there will be divergent – and certainly system-dependent – analyses of what exactly is happening during a mystical experience.

To be sure, not every mystic is concerned with analysis at all. But the variety of explanations can be dramatically illustrated by considering the perspective of a person (for example, an atheist) who denies that reality has any divine dimension. If there is no divinity, then there is nothing to experience.

Since the rise of modern psychology, it has become fashionable for atheists to explain away mystical self reports as being the result of human imagination. The idea is that somehow, purely naturalistic factors give rise, in particular people, to strong feelings or ideas that delude them into believing in divinity.

However, it’s important to realize that variation does not just appear between theists and atheists. It also surfaces within and among the diverse forms of theism and religious belief themselves.

For instance, since Neoplatonism tends toward pantheism, it is natural to take a true experience of the One as a literal, metaphysical union of the mystic with the Absolute. The mystic directly experiences the fact that, reality is interconnected, continuous, and – ultimately – an emanation from the One.

This is significantly different from the point of view of a Gnostic who believes that matter is evil. For whatever it means to have a mystical experience of the supreme deity, the Monad, it must include detachment from anything physical.

We might put the difference this way. For the Gnostic, mystical experience occurs when a human soul – which fell from a higher realm – begins its ascent to the One at the point when it is able to separate from matter.

Neoplatonic “return,” on the other hand, begins with – and in a sense includes – matter. The human being emanated from the One, body and soul. And the ascent of the human person begins right where we find ourselves: immersed in a realm of physical entities.

It is also crucial to appreciate that not all mysticism need be understood as an absorption of a soul or spirit into the divine. It is also possible to think of such experiences, in more traditionally “theistic” terms, simply as the approach of a human being to a God that is ontologically distinct.

The rub is that, for certain writers, it is sometimes hard to interpret just what sort of mysticism is being espoused or represented. For example, take the 13th-14th-c. mystic known as Meister Eckhart. His language is susceptible to multiple interpretations. For example, in one place, Eckhart declares: “When the Divine Light penetrates the soul, it is united with God as light with light.”

Now, Eckhart was a member of the Dominican religious order, the same order to which Thomas Aquinas belonged. So, some interpreters have concluded that Eckhart was a faithful Catholic whose language, where potentially problematical, should be viewed as metaphorical or poetic. On this view, when Eckhart talks of the soul uniting “…with God as light with light,” he’s just using figures of speech to convey the intimacy of a meeting that could be reported in theologically orthodox words instead.

On the other hand, other interpreters take Eckhart more literally. These people may point out that the “light with light” language suggests that both God and the soul are – so to speak – “made out of the same stuff.” In philosophical lingo, Eckhart seems to be saying that they share an essence. Or, at least it may be suspected that the boundary between God and the soul is somehow obliterated. After all, when light “mixes with” light, it is not obvious that there remains any meaningful way of distinguishing the two lights afterward.

Perhaps the lesson, here, is like that which (I suggested) applied to Hermeticism. To be more precise, it is possibly best to think of Mysticism as a practical approach to the divine – or an attitude of wanting to have a particular, intimate experience of God – the specifics of which can only be understood in the context of a particular worldview. So, there would be Neoplatonic Mysticism, Gnostic Mysticism, Traditional Christian Mysticism, and so on.

- Kabbalism

Of course, it is necessary to acknowledge that not all Mysticism has a Christian complexion. Many forms did (or do) have this orientation – such as the Catholic Mysticism of St. Francis of Assisi and the religious order (the Franciscans) that bears his name, or the Lutheran Mysticism of Johann Arndt and the German Pietism that he helped to inspire.

But, there are innumerable sorts of Mysticism that lie outside this framework, just as there were both Christian Neoplatonists (such as the 5th-6th-c. Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite) as well as non–Christian ones (like the 4th-c. Roman Emperor Julian the Apostate).

Two main streams of non-Christian Mysticism – one of which we will do no more than simply list, here – are those that exist in the other so-called “great monotheistic religions” of Judaism and Islam. (There are also other sorts that grow out of Eastern religions, such as Buddhism and Hinduism. But, here, we will restrict ourselves to a Western variety of Esotericism.)

Islamic Mysticism, a main variety of which is called Sufism, will have to occupy us another time. For it is arguable that the tradition with the greatest impact on Western Esotericism has been that which flourished within Judaism, and whose main relevant current is referred to as “Kabbalah.”

A more detailed treatment of this complicated system will be forthcoming. Although we note that Kabbalah has interacted and intersected with Christianity, for the present, suffice it to say that Kabbalah can be thought of an outgrowth of the earlier Jewish-mystical tradition known as “Merkabah.”

Merkabah, which word means “chariot,” involves contemplation – and attempted replication – of the vision of God beheld by the Hebrew prophet Ezekiel, as recorded in the opening chapter of the Biblical book bearing his name.

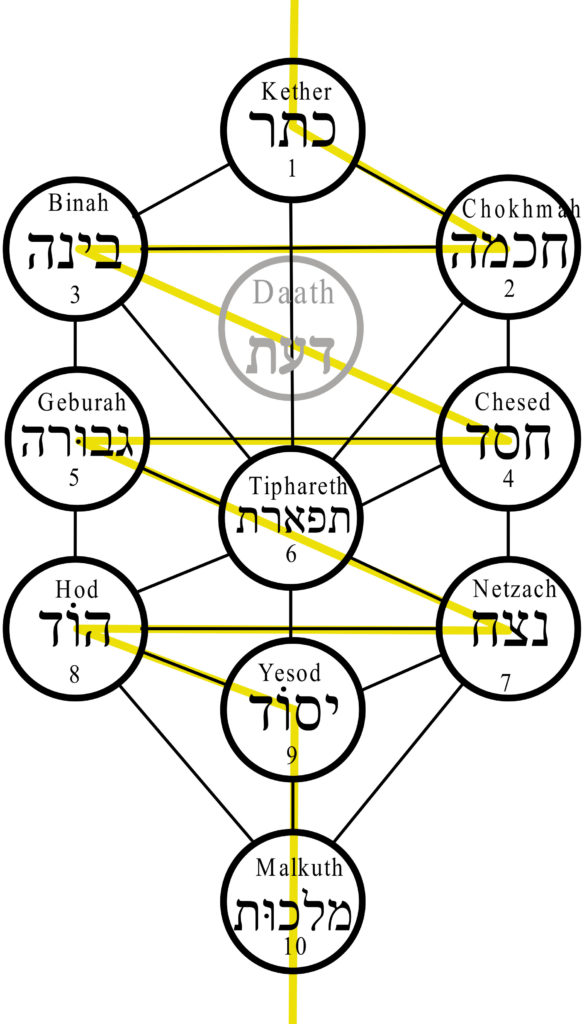

In addition to this mystical strain, Kabbalah also evolved around cosmological speculations. For example, in the Sefer Yetzirah (that is, the “Book of Formation”), the world is explained as having arisen from the Hebrew language. The twenty-two letters, along with ten numerical correspondences, referred to as “Sephiroth,” are described as comprising the “thirty-two paths of wisdom” by which God created the world.

However, this basic framework would be developed by later writers. The Sefer Ha Bahir (or, the “Book of Illumination”) introduced a Hebrew version of the idea of divine emanation that we encountered first in our discussion of Neoplatonism. Though, in the Bahir, the overall orientation is often said to be more reminiscent of Gnosticism.

Perhaps the most important text in Jewish Mysticism is the Sefer Ha Zohar (variously translated as the “Book of Radiance” or the “Book of Splendor”). The Zohar is actually a collection of texts, rather than a single one. But, in general terms, the Zohar offers allegorical or esoteric commentaries on the Five Books of Moses (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy), also called the Pentateuch.

The Zohar was first publicized in Spain by Rabbi Moses de León. For his part, de León credited the 2nd-c. figure Shimon bar Yochai with its authorship, though modern scholarship largely discounts this claim. Regardless of its provenance, it unquestionably helped to shape Iberian Kabbalah which, in turn, was imported into the Christian world after Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella expelled the Jews in the 15th century.

Thereafter, arises a stream of thought called “Christian Cabala.” In this tradition, people such as Pico della Mirandola and Johannes Reuchlin sought to show that esoteric Judaism and Neoplatonic Christianity could be seen as coinciding. Many of these theorists held to the Hermetic notion that there had once existing an “Ancient Theology,” or prisca theologia, that was the source for all subsequent religions – many of which had perverted its true doctrines.

Another important development in Jewish Esotericism occurred in the sixteenth century when the Rabbi Isaac Luria further embellished the ideas in these foundational Kabbalistic texts. Luria articulated an elaborate account of the origin of the universe whereby God – referred to in a Neoplatonic manner as the “Infinite,” or Ein Sof – “contracted” Itself to make space for the finite world. What follows is a jargon-laced cosmogony that could be read as an attempt to reconcile the Biblical story of creation with the esoteric concept of emanation.

The overall system, known as Lurianic Kabbalah, has been influential for centuries – including exerting a profound effect on later Christian Cabalists like Franciscus Mercurius van Helmont and Christian Knorr von Rosenroth, and the Pietist Swedenborgian Friedrich Christoph Oetinger.

In fact, Kabbalah generally has exerted a strong influence upon later associations like Freemasonry.

However, to its rabbinic advocates, the full exposition and presentation of Kabbalah has conventionally been reserved for insiders and specialists.

Fast forward to 20th-c. America, where Rabbi Philip Berg’s Kabbalah Centre undertook the popularization of many basic Jewish-esoteric concepts. His efforts provoked strong reactions – both pro and contra – from more traditional practitioners. Still, before his death in 2013, the Los Angeles, California-based Kabbalah Centre managed to attract A-list figures from the world of entertainment, including actress Demi Moore and singers Britney Spears and Madonna.

- Theosophy

On the topic of “movements that attracted celebrities,” we may as well go on to briefly discuss Theosophy. Following its inception in 1875, it enticed littérateurs and poets George William Russell and William Butler Yeats. It drew in Indian nationalists Mohandas Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru. Famed American inventor Thomas Alva Edison was reportedly a member, as was pioneering psychologist and philosophical pragmatist William James. One of the Society’s early presidents was the curious career military man Abner Doubleday who, among other things, was once credited with the invention of the game of baseball.

You will recall that we encountered the word “Theosophy,” previously. We noted that the Theosophical Society, founded (or, more precisely, co-founded) by Helena Blavatsky was, in part, a restatement of Gnosticism that became a major tradition in the 19th-c. “Occult Revival.”

But the word “Theosophy” may be a bit tricky.

In common usage, it frequently refers to a syncretistic system of thought that Blavatsky pioneered in books such as Isis Unveiled and The Secret Doctrine. From here, things get a bit murky, however.

Early on, her society, which was originally established in New York City, split. One co-founder, William Quan Judge, remained in the United States, while Blavatsky herself, along with Henry Steel Olcott, removed to the city of Adyar in India.

Additionally, following Blavatsky’s death, British political activist Annie Besant and her associate, an ex-Anglican priest named Charles Webster Leadbeater, would modify some of the Society’s initial teachings – so much so that some of those wishing to remain loyal to their foundress would label their variant doctrines “Neo-Theosophy.”

The Theosophical Society also inspired the creation of other systems, which are sometimes grouped under the “Neo-Theosophy” heading. This would include Rudolf Steiner’s “Anthroposophy” – which word refers to “human wisdom” and which goes back to the writings of the 16th-c. German magus Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa and the 17th-c. Welsh alchemist Thomas Vaughan.

However, viewers should be aware that that same term – Neo-Theosophy – is also sometimes applied to the writing of “channeler” and seminal New-Age thinker, Alice Bailey. Bailey was affiliated with the Theosophical Society for a time. Although she was supposed to have been an important spokesperson for a drive to return it “back to Blavatsky,” she eventually broke with the Theosophical Society and, with the backing of her second husband, Foster, articulated her own form of Esotericism.

Similarly to Blavatsky, Bailey claimed to be in telepathic communication with an alleged Tibetan “Master.” From these extrasensory “dictations,” Bailey derived a worldview that incorporated elements of esoteric astrology, Gnostic cosmology, “Hermetic Qabalah,” and much else besides.

Via Foster Bailey’s Lucis Trust, Alice Bailey launched her Arcane School which has had a pronounced effect on Western versions of ceremonial magic, neo-paganism, the New Age Movement, parapsychology, and various forms of “psychic” or “energy” healing, such as Reiki and Shiatsu.

Although the word “Theosophy” is perhaps most frequently used as a proper name for Blavatskian Esotericism and its many offshoots – some of which were just rehearsed – there are two further complications.

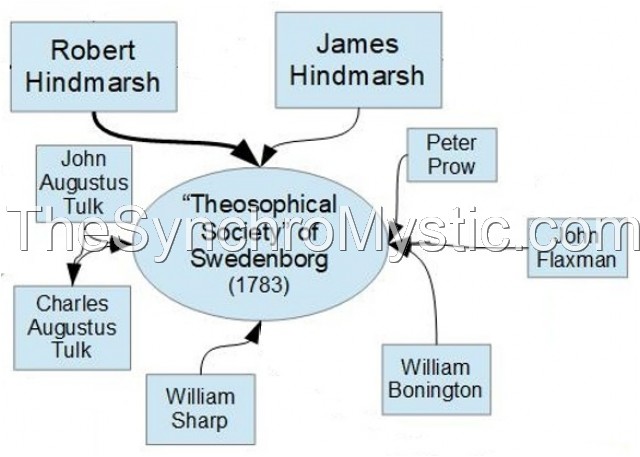

Number one, it turns out that there was a group calling itself the “Theosophical Society” roughly a century years before the inception of its better-known, 19th-c. counterpart.

The previous incarnation was formed in London by a group of English admirers of the 17th-18th-c. Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg. The circle of Swedenborgians was instituted by James and Robert Hindmarsh and included British artists John Flaxman and William Sharp.

Number two, we observe that the word “theosophy” may also be used as a common noun.

Strictly speaking, the word means the “wisdom of God.” Because of this, one sometimes encounters references to “theosophy” in regard to systems of thought and to thinkers that predate either Blavatsky’s or Hindmarsh’s societies.

For example, historian Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke refers to both Hermeticism and Behmenism as “theosophical,” even though the former may go back as far as Hellenistic Greece (or, if you believe the legends, even earlier) and the German mystic Jakob Böhme died in 1624.

The previously named Lutheran-Swedenborgian, Friedrich Oetinger, is routinely called a “theosophist” because of his attempts to fuse his Kabbalistic-Christian mysticism with natural science.

Furthermore, at least one online dictionary defines “Kabbalah” itself as “an esoteric theosophy of rabbinical origin based on the Hebrew scriptures and developed between the 7th and 18th centuries.”1

Or, again, and as cursory visits to the relevant Wikipedia articles will reveal, similar descriptions are sometimes applied to the spiritual tradition set in motion by the Dominican preacher Meister Eckhart, and carried forward by Johannes Tauler and Henry Suso, and – later – the Protestant Valentin Weigel.

Finally, the Theosophical Society itself could be considered an occult-science institution, as two of the “three objects” of that association, as articulated in the early 20th century, make clear. Therefore, “theosophy” – in some contexts – could be considered a synonym for occultism.2

- Spiritualism

My reference to a “spiritual tradition” segues us to our next word, Spiritualism.

Of course, the way I just employed it, “spiritual” simply means “religious” or “church-related.” But there are further, more specialized, meanings that you should be aware of.

One definition for “Spiritualism” treats it as an antonym for philosophical materialism. We’re not speaking, here, about a preoccupation with money and worldy goods – in the way that the previously mentioned Madonna referred to herself as a “Material Girl” in a popular song from the 1980s.

Crudely stated, “materialism,” in our sense, is the view that only matter exists. Materialism is often characterized as a modern revival of a philosophical doctrine called “atomism,” which owes its initial formulation to the ancient Greek thinkers Leucippus and Democritus.

Modern materialism is attributed to the 17th-c. French Catholic astronomer and priest Pierre Gassendi and is explicitly defended by his contemporary, the English political philosopher Thomas Hobbes.

The idea that reality is exclusively made up of matter – and not anything like mind or spirit – became a powerful stream in some Enlightenment thinkers, for example, the French encyclopedists Denis Diderot and the Baron d’Holbach.

In contemporary terms, the advent of energy physics prompted a reconfiguration of the view. Hobbes’s current intellectual heirs now routinely call themselves physicalists, rather than “materialists” per se. This is registers the facts that (1) energy is not obviously “material” (even if energy and matter are interchangeable). But, even so, (2) both energy and matter are, nevertheless, physical.

In protest to this sort of reductionism, there are those who believe in the separate existence of mind or spirit, as distinct from anything physical. In this broad way of talking, “spiritualism” could be considered a way of referencing these anti-materialist perspectives. As such, the word would be a close cousin to “Idealism,” “Panpsychism,” “Romanticism,” and so on.

But, as a technical term in the study of Esotericism, the word “Spiritualism” most often picks out something different. To get a fix on it, we have to turn back to the 19th-c. Occult Revival that we discussed a few minutes ago.

This sort of Spiritualism has to do with so-called “mediumship.” This is the idea that certain attuned people, called “mediums,” are able to “channel,” or otherwise communicate with, the spirit world. For those who go in for it, this realm is usually thought of as populated with the souls of dead people.

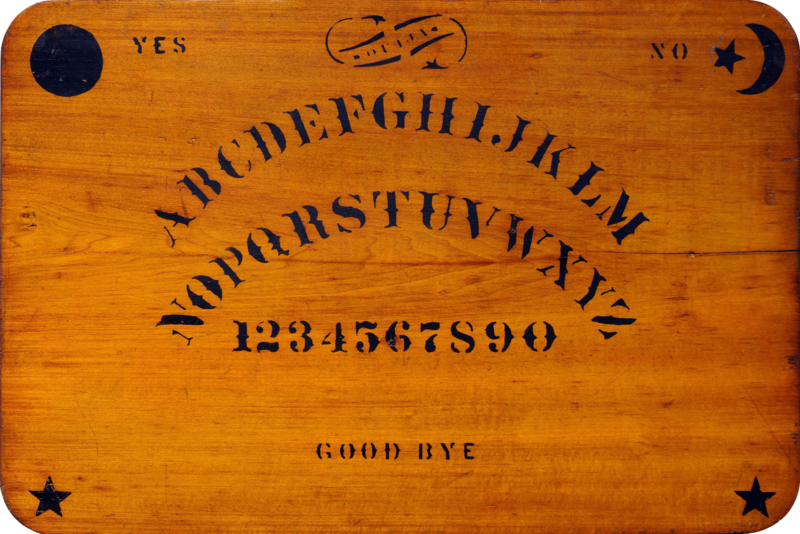

One practice, known as a séance, involves a group of participants sitting around a table. The medium attempts to establish the desired spirit contact, perhaps by entering into a trance or by using various props, like the device now known as a “ouija board.”

Devotees hold that, when a successful connexion is made, the spirits frequently produce sense-perceptible evidence of their presence. These may come in the form of lights flickering or heard noises such as “table rapping.”

Some mediums were believed to undergo physical changes during a spirit manifestation. An example of this is the alleged generation of a curious substance called “ectoplasm,” which was said to be materialization of a spirit’s energy and was used to comic effect in the 1984 movie Ghostbusters, featuring actors Dan Aykroyd, Bill Murray, and Harold Ramis.

Although there were antecedents, not least of which include the “animal magnetism” therapies of Franz Anton Mesmer and the mystical writings of Emanuel Swedenborg, Spiritualism properly so-called is typically dated to the mid 1800s.

At that time, numerous claimed mediums and Spiritualists – including Kate and Margaret Fox and Cora L. V. Scott – achieved celebrity status. Some of them – for example, Andrew Jackson Davis – were even sought after as “faith healers.”

Faith healing would later be integrated into Christian movements such as those involving Pentecostalism, “Positive Confession,” and so-called “Word of Faith” theology.

However, for all its apparent novelty, Spiritualism has been characterized as a warmed-over – and Americanized – version of Renaissance Neoplatonism, which we touched on previously.

The movement had a significant impact. It impressed such notables as British story writer Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, and Mary Todd Lincoln, wife of the ill-fated 16th American president, Abraham Lincoln.

Spiritualism carried over into the 20th century as well, in such figures as the famed clairvoyant and “New Ager” Edgar Cayce who, during trance sessions, often reported on the mysterious and possibly mythic lost continent of Atlantis.

In some quarters, interest in a wide range of occult topics, including Spiritualism, persists to the present day – as can be seen from the fact that booksellers like Amazon and Barnes and Noble continue to stock many relevant titles.

- Metaphysics

And this brings us to the last word we’ll tackle today, namely, “Metaphysics.”

For it is not at all uncommon to hear esoteric- and paranormal-themed books, practices, and theories referred to as “Metaphysical.”

Examination of the word provides clues as to why. The prefix meta– can be translated “after” or “beyond.” So, it is natural to understand Metaphysics as a discipline dealing with phenomena that somehow “go beyond” that of the everyday, mundane, physical world.

The word “Metaphysics” also shows up in academic contexts. Take note: Students enrolling in a college Metaphysics course should not expect to spend much time on “auras” or “energy crystals.”

You see, in university parlance, “Metaphysics” denotes a major branch of Western philosophy, sometimes alternately labeled “ontology.” Other outstanding subdivisions include “epistemology,” or the study of how – and whether – human beings can have genuine knowledge of anything, and “ethics,” or the study of moral decision-making, principles, values, and so on.

In the field of Metaphysics, one is concerned with abstract issues regarding existence. What sorts of things exist? What does it mean for anything to be? What is the nature of causation? These are the sorts of questions about which the philosophic metaphysician will be preoccupied.

At least… the metaphysician who has been trained in the main lines of what is termed the “analytic” philosophical tradition.

However, in the case of the word “Metaphysics,” the two definitions can dovetail in interesting ways. After all, whether spirits and the other objects of occult speculation actually exist is a perfectly fair question to ask. And the possible answers may be of interest to anyone who wishes to think seriously about it.

And that, of course, is part of the ambition of this YouTube channel. So if, like us, you are also fascinated with things like Neoplatonism, Gnosticism, Hermeticism, Spiritualism, and other avenues of Occultism, then… stay tuned for more!

Notes:

1“Cabbala” (sic), Vocabulary.com, <https://www.vocabulary.com/dictionary/Cabbala>.

2This Theosophical-Society legacy cross-pollinated with Aleister Crowley’s myriad activities, some of which might be glossed as his attempts to do “illuminated science.”