The word “occult” simply means “hidden” or “secret.”1 Throughout history a number of people have dabbled – or specialized – in disciplines that are arguably characterizable as occultic (even if for different reasons).

For this list, I’m focusing on ten real-life figures who have sometimes been classified as “occultists.”

Some have been involved in the so-called “Hermetic arts” – alchemy, astrology, and magic – while others may be more correctly viewed as esoterics or mystics. One or two were apparently mixed up in practices that were a bit, well… darker.

There is no implication that the sometimes very different beliefs of these people are necessarily related. In other words, although some of these people may have interacted with one another and they bear sometimes interesting relationships, they were unique individuals and each entry stands on its own.

But, without further ado, here are my picks for the top 10 occultists who ever lived.

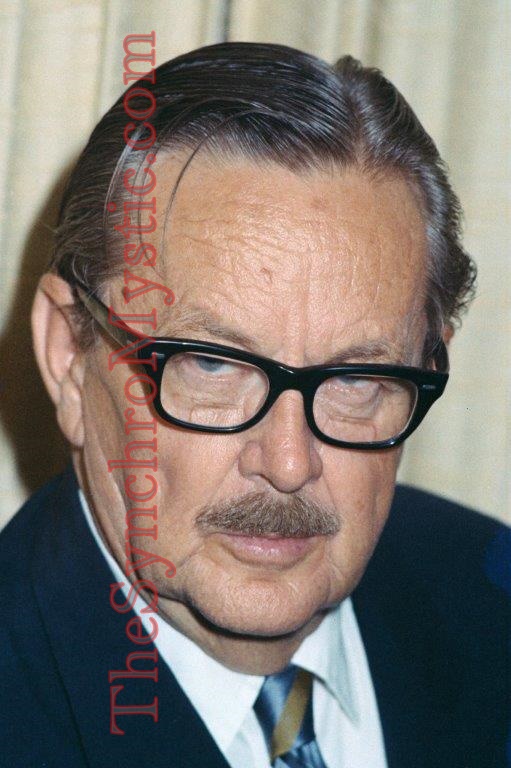

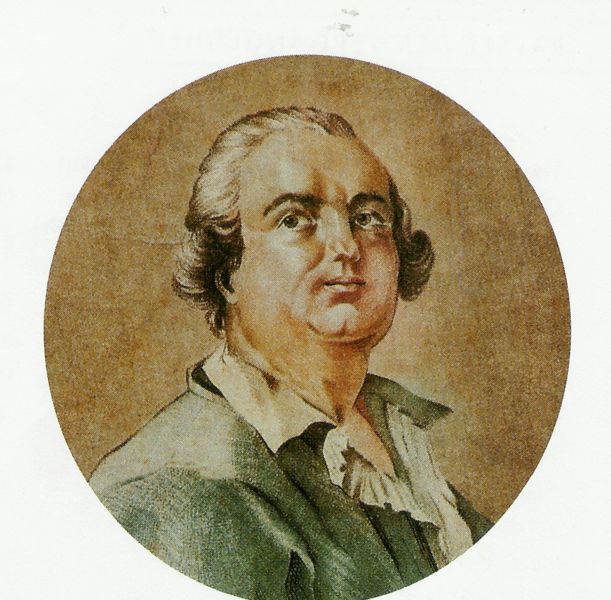

10. Cagliostro

Supposedly born Giuseppe Balsamo in 1743 in Palermo, Italy, the man who would come to be known as “Cagliostro” was surrounded by controversy and mystery for most of his life.

He was praised by admirers as a powerful magician and mesmerist as fervently as he was denounced by detractors as a charlatan or infidel.

Cagliostro appeared on the scene in London in the momentous year 1776 – the same year the United States issued its Declaration of Independence from the British Empire, and the same year the ex-Jesuit Adam Weishaupt, under the name “Spartacus,” started the Bavarian Illuminati.

Cagliosto claimed to have been raised on the cryptopolitically significant Island of Malta – certainly a proverbial “hot spot” in arcane geography.2

And he said that he became a “Knight” in the Catholic religious Order of Malta – which traces its origins back to the crusading Knights Hospitaller, founded in the 11th century.

But, somehow, Cagliostri made his way to England, which island nation is occasionally referred to by the mystical name “Albion.”

Scattered and possibly unreliable reports suggest that he was subsequently “made” a Freemason, perhaps at the French Loge L’Esperance, then located in London.

Cagliostro himself claimed to be in possession of fantastic occult secrets – such as the formulas for the “Water of Life” and the so-called “Philosopher’s Stone” that had been the fabled goals of alchemy for hundreds of years.

He is noteworthy, in part, because of his introduction of a so-called “Egyptian Rite” into Freemasonry. Though, this association seems to have been more Kabbalistic than Egyptian.

“Kabbalah,” of course, is a stream of mystical and numerological tradition within the religion of Judaism, mainly associated with books such as the Bahir and the Zohar.

Cagliostro’s strange brand of masonry seems to have inspired later offshoots, such as the Rite of Memphis & Mizraim,3 which (in turn) may have motivated some urban planners in the U.S. to confer Egyptian-sounding names to cities like Memphis, Tennessee.4

Although Cagliostro held various odd jobs throughout his life, he is best remembered as something of a socialite who traveled across Europe (and possibly the Middle East) hobnobbing with royalty.

This pastime later created a few problems for him, however, as he was implicated (whether falsely or not) in a jewelry swindle involving French King Louis XVI’s wife, Marie Antoinette.

The event, called the “Affair of the Diamond Necklace,” was the subject of a 2001 Warner Brothers film,5 featuring Hilary Swank, Jonathan Pryce, and Christopher Walken as Count Cagliostro.

Historically, it was a major scandal and it increased popular resentment for the monarchy – feelings that paved the way to the bloody French Revolution – which some claim Cagliostro predicted.

The scandal was a factor in the growing resentment of the French people for the monarchy and helped lead to la révolution – which bloody event some claim Cagliostro predicted.

Imprisoned in the Bastille, he was eventually acquitted. But, shortly thereafter he ran afoul of the Catholic Church’s Roman Inquisition – which had earlier executed the 16th-century Dominican Hermetic philosopher Giordano Bruno and which should not be confused with the more notorious Spanish Inquisition run by Tomás de Torquemada at the behest of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella.

Cagliostro is said by some to have died in the Castel Sant’Angelo while serving a sentence on heresy charges. Others maintain that he cracked the secret of immortality and effected a fantastic escape from his tormentors.

Either way, his memory was recently reinvigorated through his incorporation into the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Scott Derrickson’s 2016 movie, Dr. Strange, makes several mentions of a mysterious grimoire referred to in the film as the “Book of Cagliostro.”

9. Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa

Born in 1486, Agrippa would become one of the most vilified occult philosophers of the Renaissance. He is frequently represented as having been a “black magician,” and depictions of him often include a black dog – his schwarzer pudel – which beast, in the lingo of witchcraft, was assumed to have been his “familiar spirit.”

“Familiar spirits,” of course, were entities – usually appearing as animals – who were believed really to be demons or other incorporeal beings who did the bidding of magicians and witches.

Ideologically, Agrippa fits broadly into a group of thinkers who lived at a time – after the fall of Byzantine Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire and after the expulsion of Jews and Muslims from Catholic Spain – when Catholic Europe was exposed to Greek Neo-Platonism and Jewish mysticism.6

A core group of Italians, including Marsilio Ficino, Pico dela Mirandola, and Francesco Giorgi, first began to combine these disparate traditions into a cohesive new system.

On the one hand, they were operating within the umbrella of Roman Christianity which, due to its Platonic heritage, already had some mysticism – particularly as expressed in Franciscan spirituality.

It also displayed a robust Christian “angelology,” or study of angels, inherited from the writings of Pseudo-Dionysus – especially in the books De Coelesti Hierarchia (“On the Celestial Hierarchy”).

These Italians then assumed some of the metaphysical framework of the ancient Neo-Platonists.7 To this, starting with Pico della Mirandola, they added elements of Spanish-Jewish Kabbalah.

The way toward this assimilation was partially paved by a growing interest in the languages of Greek and Hebrew8 – first by various religious orders, including the Cistercians, Dominicans, and the Franciscans mentioned a moment ago, and, later, by Renaissance Humanists, such as Petrarch, Macropedius, and Erasmus.

Into this “Christian Kabbalah,” Agrippa and others further mixed what they perceived to be the ancient Hermetic traditions of the legendary Hermes Trismegistus – in the form of the newly rediscovered and translated Corpus Hermeticum.

They believed that they were bumping up against a prisca theologia (that is, an “old theology”) – perhaps one that had been delivered to some of Biblical figures such as Enoch or Adam.

The aim was to reconcile all religious traditions and philosophies – including those that promoted the use of magic – a goal later adopted by H.P. Blavatsky.

For Agrippa, magic permeates the entire world, which he divided into three “realms”: the elemental world of earth, the sphere of planets and stars, and the “intellectual” plane of the divine.

Each division of the world has its own associated magic: “natural” or herbal magic at the terrestrial level; mathematical magic at the celestial level, and ceremonial magic at the super-celestial level.

The numerological character of some of this – as seen, for instance, in the use of magic squares – had a decided Pythagorean flavor, borrowed partly from fellow Kabbalist and occultist Johann Reuchlin.

Each of the cosmological levels is superintended by angelic entities – of varying degrees of power; and each type of magic has its own astrological correspondences – which exemplify the alchemical as-above/so-below maxim. Some of this this will be echoed by Aleister Crowley in the 20th century.

And this represents one of Agrippa’s most biggest contributions to what historian Frances Yates calls the “Hermetic-Cabalist tradition”: namely, Agrippa introduces alchemy into the mix.9

Yet, extraordinarily, Agrippa seems to have conceived of all this as a species of Christianity – chiefly because he recognized the name “Jesus” as the highest of the words of power.

Agrippa’s De Occulta Philosophia (“The Occult Philosophy”) was first printed in 1531 and would have a profound effect on later esoterics and would-be magicians – including those like Arthur Edward Waite who comprised the memberships of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.

Agrippa is memorialized with references in Christopher Marlowe’s play The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus (circa 1590), and in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818).

8. John Dee

If Agrippa represented the migration of Italian occultism to Germany, John Dee represented its arrival in England.

Dee was born in the tumultuous 16th century, when the Reformation seesawed his country back and forth from Catholicism to Protestantism.10

During this time, partly in the capacity of a “royal astrologer,”11 he was variously in and out of favor with an assortment of well-to-do patrons, including some of the English monarchs of the period.

Widespread belief in his ability to produce or “cast” a horoscope made him a much-sought-after personality during this age of political intrigue.

However, this renown was a double-edged sword. John Dee would spend time in prison and, eventually, die in obscurity, because of his affiliations and views.

During his life, Dee worked closely with an alleged clairvoyant or medium named Edward Kelley.

Sounding a note from Agrippa, together, Dee and Kelley engaged in various alchemical experiments – including the attempt to create gold from base matter.

They also picked up on some of the early-medieval angelology12 and made various attempts at “scrying,” that is, they tried divination using a crystal ball or similar paraphernalia – such as Dee’s obsidian “spirit mirror.”13

But, Dee is mainly remembered as having been something of a sorcerous character. And, indeed, at one time or other he owned several “grimoires” – or books of spells – including the Book of Soyga,14 the Fourth Book of Occult Philosophy (falsely attributed to Agrippa),15 and the Sworn Book of Honorius.16

John Dee entertained socio-religious aspirations of a worldwide occultic-evangelical movement with Queen Elizabeth at the head – a view echoed by English poet Edmund Spenser in his epic The Faerie Queene (published around 1590).

Ostensibly to further this end, Dee visited Europe to spread his new “faith.”17

In any event, Dee and Kelley first met Polish King – and Transylvanian Prince – Stephen Báthory, uncle of the notorious, accused female serial murderer and torturer, Elizabeth Báthory.

Subsequently, the duo traveled to Prague in the Kingdom of Bohemia – now the capital of the Czech Republic – and visited the court of Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II.

Rudolf was well-known as a patron of avant-garde art,18 alchemy,19 and astrology.20 These pastimes brought numerous, curious personalities to Rudolf’s court, including alleged “prophet” Nostradamus,21 alchemist Michael Sendivogius,22 and Rabbi Judah Loew23 – who, legend has it, created a soulless, moving creature (called a “Golem”) out of clay.

These forays into geopolitics appear to have been mostly fruitless – possibly because Dee was regarded as an Elizabethan spy. Indeed, British journalist Donald McCormick, writing in 1968 under the pseudonym Richard Deacon, asserted that Dee was involved in espionage for the Crown and that he signed his correspondence “007.”24

However, after the death of Queen Elizabeth, who had been Dee’s faithful protector against lifelong allegations of heresy and sorcery, he fell out of favor with reputed “witch hunter” and Stuart King, James I (namesake of the King James Bible).

As a result, Dee died in poverty and the exact date of his death is unknown. (It was sometime either in 1608 or 1609.)

He was even left largely friendless, as he and Edward Kelley had had a falling out – possibly due to curious instructions they had received from a spirit who told the pair to swap wives (which, apparently, they did).

At the same time, something of his specter lives on.

For example, playwright William Shakespeare incorporated a Dee-like character – Prospero – into The Tempest (first performed in 1611).

On the modern scene, in H. P. Lovecraft’s short story “The Dunwich Horror,” we read that one of the characters possesses a copy of the Necronomicon that was a “priceless but imperfect copy of Dr. Dee’s English version” of that fabled document.25

Another, separate trajectory of Dee’s influence lies in so-called “Enochian magic.”26

This complicated system derives from the efforts of Dee and Kelley who claimed to have obtained it directly from contact with various angels.

It involves the use of a dedicated alphabet, referred to as “celestial speech,” and which was – according to Dee – the language spoken by the biblical Adam up to the time of Enoch.

Fascination with discovering the lingua Adamica (or, “Tongue of Adam”) was not unique to Dee. Other writers of the period, including the French mathematician and philologist Guillaume Postel, also speculated about the language that had been spoken in the Garden of Eden.

Postel, however, seems to have advanced the possibility that either some form of ancient Chaldean or Hebrew had been the mother of all subsequent dialects.

Finally, John Dee’s influence can be traced through the 19th-c. “occult revival” – for example, as manifested in the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, which billed itself as a sort of “academy for magicians”27 – and 20th-c. developments such as the “Chaos Magic,” associated with people like Peter Carroll, Phine Hine, and Austin Osman Spare.

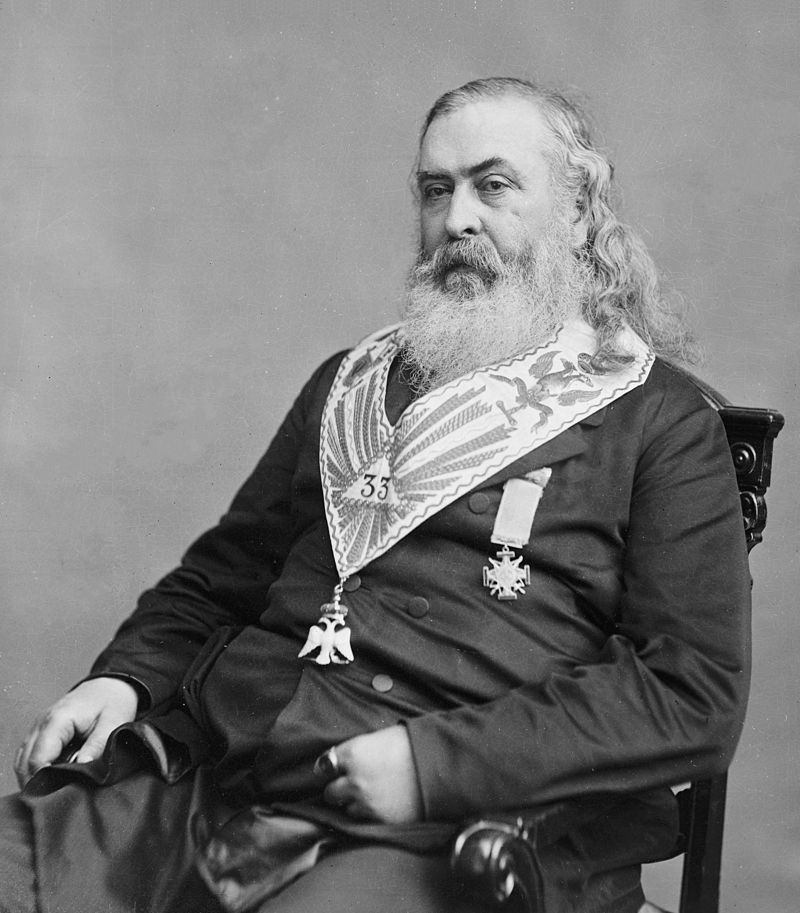

7. Albert Pike

Albert Pike was a 19th-c. American Confederate general and lawyer who is best remembered for having served as Sovereign Grand Commander of the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry.

Born on the East coast, in Boston, Massachusetts, he spent considerable time in Arkansas – both before and after it was admitted into the United States.

Pike’s politics were a complicated amalgam. On the one hand, he advocated for Native Americans (then referred to as American Indians). On the other hand, he was known to have held anti-Catholic and pro-slavery views28 for much of his life.29

Among Pike’s primary masonic objectives was the reconfiguration of various “rituals” used by the fraternal order for initiatory and other purposes.

In general terms, “masonic ritual” refers to the particulars – including, actions, symbols, and words – pertaining to these ceremonies.

Similarly to John Dee, Pike had an expansive library on esoterica and the occult. Much of this collection was reportedly amassed in order for him to discharge his task of re-imagining freemasonry’s allegorical, historical, and spiritual framework.

The result of this highly influential – and admittedly monumental – effort (or, at least, Pike’s notes regarding his investigations) was the somewhat tedious tome, Morals and Dogma of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry (Charleston, S.C.: n.p.), first published in 1871.

During the course of his investigations, Pike surveyed – and arguably attempted to harmonize – “…the philosophies of the Gnostics, the Hebrews, the Alexandrians, the Druids, …the Essenes, …[and] the mysteries of Egypt, Persia, Greece, and India…”.30 – Quite a hefty undertaking.

His book became so important – at least in the Scottish Rite – that anti-Masons (among others) frequently refer to it as the “Bible of Freemasonry” – though practitioners of the “Craft” may usually be replied upon to disclaim this lofty designation.

Still, it is undoubtedly Pike’s magnum opus, and it would exercise some influence over Manly P. Hall, who would become one of the foremost Masonic theorists in the 20th century. According to Obadiah Harris,31 former director of Hall’s Philosophical Research Society in Los Angeles, no less a figure than President Franklin D. Roosevelt – himself a Freemason – was aware of Hall’s work and so, by extension, was influenced by Albert Pike.

6. Madame Blavatsky

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky32 was a Russian/Ukrainian-born esoteric and writer who co-founded the Theosophical Society.33

A key aspect of Blavatsky’s system is its Eastern-mystical flavor.

To her, the kind of Renaissance Kabbalistic Neoplatonism canvassed earlier when discussing Agrippa had not gone quite far enough in trying to excavate and explicate what (she believed) was an ancient wisdom tradition that had once existed all over the earth.

To the end of articulating such a Secret Doctrine – the title of her 1888 multi-volume book – and managing a “Synthesis” of all “Science, Religion and Philosophy,” Blavatsky turned her eyes Eastward and borrowed numerous teachings from the religions of Buddhism Hinduism.34

Her first attempt at articulating her amalgamated Theosophy (which word, of course, means the “wisdom of God”) was in her book Isis Unveiled,35 complete with a subtitle claiming that her system was A Master-Key to the Mysteries of Ancient and Modern Science and Theology.36

According to Blavatsky, a hidden group of adepts – sometimes referred to as “Ascended Masters” or “Mahatmas” – are custodians of this arcana and steer humankind from behind the scenes.37

She claimed personal acquaintance with several of these entities and later dropped two curious names: “Kuthumi” and “Morya,” stating that these entities resided in or near Himalayan Tibet.

According to historian Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, Blavatsky’s influence extends both to the Occident and to the Orient.

For example, “…[Mohandas] Gandhi and [Jawaharlal] Nehru…” – both figures in the Indian independence movement – “…were drawn to Theosophy to rediscover their own religious and philosophical heritage.”38

Goodrick-Clarke goes on to say: “In the West, Theosophy was perhaps the single most important factor in the modern occult revival.”39

Blavatsky repackaged the notion of “…Hermetic …correspondences between the macrocosm and microcosm” in contemporary lingo.40 For example, she arranged her spiritual principles on an evolutionary framework, aligning Theosophy with prevailing anthropological, biological, and cosmological scientific language.

She maintained that our “individuality” will “…[pass] through all forms of existence …until we achieve complete union with spirit” – the One, Absolute, Monad, etc.41

Relatedly, Theosophy appears to have a cyclical view of history. Furthermore, at least as communicated by present-day adherents, Blavatsky’s schema teaches a universal “oneness” of all reality in what is probably best described as a form of pantheism – or, the belief that everything is divine.

Additionally, and in line with her syncretism, Blavatsky was committed to the now-pervasive idea that all religions point – to greater or lesser degrees – to a single body of truth.

Her influence can further be seen in the fact that distinctively Buddhist and Hindu religious concepts (which Blavatsky held in high regard) have gained wide acceptance outside of India.

For instance: “Several polls carried out in North America and Europe show that the professed belief in reincarnation is widespread. Roughly twenty percent of the interviewees …state that they have wholly or partly adopted a belief in reincarnation.”42 And this was over fifteen years ago!

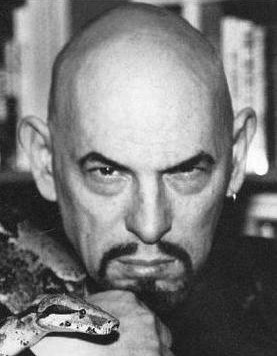

5. Anton LaVey

Born Howard Stanton Levey, the man who would become known as Anton Szandor LaVey is best remembered for founding the Church of Satan in San Francisco, California on April 30, 1966 – which date is regarded as the “Satanic holiday” Walpurgisnacht.

LaVey is a difficult character to get a fix on. More than anything, he seemed to be a performer or showman.

LaVey claimed to have been cast in an uncredited role43 as Satan for the sex scene in Roman Polanski’s demonic horror classic, Rosemary’s Baby.44

Although released in 1968, the film was set during the end of 1965 and the beginning of 1966, which latter year LaVey had declared the inaugural year for the “Age of Satan.”

LaVey advanced his points of view in several books, including The Satanic Bible in 1969,45 The Compleat Witch in 197146 (which was retitled The Satanic Witch and published by Adam Parfrey in 198947), and The Satanic Rituals in 1972.48

At times, his brand of Satanism appears close to endorsing the notion that the “Devil” is to be understood as some hidden enlightening, progressive “force.” Though, representatives are quick to disclaim any belief in any sort of “supernaturalism” – including belief in God or the Devil as personal entities.49

At other times, however, one gets the impression that talk about Satan was merely a colorful way of expressing a Do-Your-Own-Thing ethos, in the pattern of Francois Rabelais and Aleister Crowley that we’ll discuss further in a few minutes.

Alternatively, a person might get the impression that some of LaVey’s words and actions were merely intended to lampoon or parody religious belief – particularly the convictions of Catholic-Christians.

In this spirit of mocking jest, LaVey’s writings could be viewed as an extension of the kind of profanity on display in the 12th-c. Carmina Burana liturgical satires or, later, the bawdy and debauched tomfoolery associated with 18th-c. English government minister Sir Francis Dashwood’s Hell-Fire Club.

The Hell-Fire Club was a diabolically themed gentleman’s club that counted among its members many British statesmen and even, reportedly, American Founding Father Benjamin Franklin.

In the 20th century, LaVey’s Satanic church would also attract celebrities – among whom were African-American entertainer and “Rat Pack” member, Sammy Davis, Jr., as well as actress and sexpot Jayne Mansfield.

In any case, and for its part, the current church disclaims illegal or otherwise nefarious goals, stating: “Let us …look at contemporary Satanism for what it really is: a brutal religion of elitism and social Darwinism that seeks to re-establish the reign of the able over the idiotic, of swift justice over injustice, and for a wholesale rejection of egalitarianism as a myth that has crippled the advancement of the human species for the last two thousand years.”50

LaVeyan Satanism may be understood as concentrating upon – and exulting – the individual and his or her will. In this way, it may be seen as an outgrowth and modification of the philosophies of thinkers such as Friedrich Nietzsche’s “will to power,”51 Arthur Schopenhauer’s Wille,52 Ayn Rand’s “Objectivism,”53 and Aleister Crowley’s “Thelema.”54

4. Éliphas Lévi

However, another of LaVey’s influences – or, at least, another of his precursors – was the 19th-c. “magus,” Alphonse Louis Constant, more usually referred to as Éliphas Lévi – sometimes pronounced more like /ELL-i-phus LEE-vie/ by anglophones.

He had a peculiar career. For example, he started out on a path towards becoming a Roman Catholic priest, even going as far as taking some of the requisite vows. However, his partiality for Gnosticism put him at odds with church hierarchies dominated by the anti-modernist Popes Gregory XVI55 and Pius IX.56

Lévi may also have had some fairly politically subversive opinions. This is perhaps not surprising given that he lived at a time characterized by the rise of political liberalism.

That he was viewed as something of a “radical” is evidenced by his imprisonment shortly after the publication of his La bible de la liberté (“The Bible of Liberty”).57

Lévi is sometimes said to have been influenced by socialism, perhaps somewhere in between the “New Christianity” of Henri de Saint-Simon and the “Utopianism” of Charles Fourier.

American-born esoteric writer Arthur Edward Waite, one of the preëminent occultists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, translated and condensed some of Lévi’s system.

Many of these references are still widely available in reprint editions – including Waite’s volume The Mysteries of Magic: A Digest of the Writings of Eliphas Lévi published in London by George Redway in 1886.

Lévi picked up on several, preëxisting undercurrents.

For one thing, his magical system depends heavily on an alleged grimoire known as the “Greater Key of Solomon” – referring to the biblical, Israelite monarch who, according to legend, had knowledge of how to command demons.

Lévi explains the potency of magic in terms of “imagination” and “will” – both concepts traceable to Medieval Scholasticism and found, in modified form, in Renaissance occultism.58

Cosmologically, he latches onto the alchemical-Hermetic notion of microcosmic/macrocosmic “correspondences” – a constellation of ideas also found in the Kabbalah.

Lévi seems to have been influenced by a wide range of Jewish-influenced Christian and pseudo-Christian mystics going back to the 13th-c. Majorcan thinker Ramon Lull and extending through to 18th-c. Swedish philosopher Emmanuel Swedenborg and 18th-19th-c. French composer Antoine Fabre d’Olivet (an-TWAN FABRI-dole-ee-vay).

Moreover, he appeared to want to repackage and syncretize the “herbal magic” of Paracelsus – as it had passed through Rosicrucianism – with a modernized version of Agrippa’s “ceremonial magic,” filtered through the 18th-c. English occultist Francis Barrett, particularly in his book, The Magus, or Celestial Intelligencer.59

But Lévi’s real significance arguably lies in the fact that he was the “first to connect the Cabala with fortunetelling Tarot cards.”60

From this insight, Lévi extrapolated a complex series of linkages between the letters of the Hebrew alphabet and the Tarot “Trumps.” This picks up the linguistic note sounded by John Dee, and others, and is later echoed by Arthur Edward Waite in his famed Rider-Waite Tarot deck, about which I will have more to say in a subsequent video.

On the literary front, among those who “admired” Lévi was Victorian author and politician Lord Edward Bulwer-Lytton.61 Although largely unknown today, Bulwer-Lytton originated several still-used phrases such as “it was a dark and stormy night,” which was the opening line of his 1830 novel, Paul Clifford.62

Lévi’s primary influence was exercised upon subsequent occultists such as Madame Blavatsky, the Golden Dawn, and the Masonic philosopher Manly Palmer Hall.

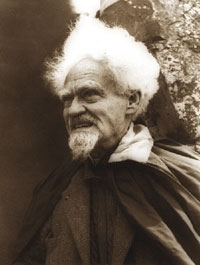

3. Gerald Gardner

The late-19th to early 20th-c. occultist born Gerald Brosseau Gardner was to exercise a tremendous impact on the reintroduction of “witchcraft” – first to the United Kingdom and, later, to the rest of the world.

Although Gardner was born into a fairly well-to-do family that had become prosperous in the lumber business, he appears to have been cast aside and left in the care of a somewhat aloof nursemaid.

After a time, Gardner’s nanny married a man who owned a tea plantation in Sri Lanka, where she moved taking young Gerald with her.

Gardner apparently learned the business and was successful enough at it to have the luxury of extensive travel and, eventually, an early retirement.

While in the east, Gardner familiarized himself Malaysian native religions.

And, although he was never formally educated, over the course of his life he read numerous esoteric-themed books including Charles Godfrey Leland’s folklore collection Aradia; or, The Gospel of the Witches,63 Florence Marryat’s 1891 Spiritualist classic There Is No Death64 and Margaret Murray’s seminal, though highly eccentric and heterodox, anthropological treatise The Witch-Cult in Western Europe.65

Additionally, at one time or other, he appears to have been a member of various secret societies, including Freemasonry and Rosicrucianism.

The consensus scholarly opinion has it that these resources, along with his own experiences with diverse traditions (from Buddhist and other ceremonial-magic practices on the one hand to folk herbalism and paranormal speculations on the other), coalesced into what became known as Wicca.

However, according to his own account, Gardner had been initiated into an an ancient Anglo paganism by a mysterious witch he referred to as “Old Dorothy.”

Regardless of its source, Gardner popularized Wicca through numerous avenues, for example, by writing about it in several books such as High Magic’s Aid 66 (published pseudonymously in 1949, two years before the repeal of the Britain’s Witchcraft and Vagrancy Acts that would have made his practices illegal), as well as Witchcraft Today67 in 1954 and The Meaning of Witchcraft68 in 1959.

Beyond this, the so-called Book of Shadows – originally Gardner’s working notes – is now also widely available and is held in high regard by some Wiccans.

If recent headlines can be believed,69 Gardnerian Wicca itself is among the fastest-growing religions in America and Great Britain, and, in any case, it has helped to give motivate a resurgence of neo-paganism more generally – a broad designation ranging many associations and movements that, besides Wicca, include Druidism, Heathenry, and Odinism.

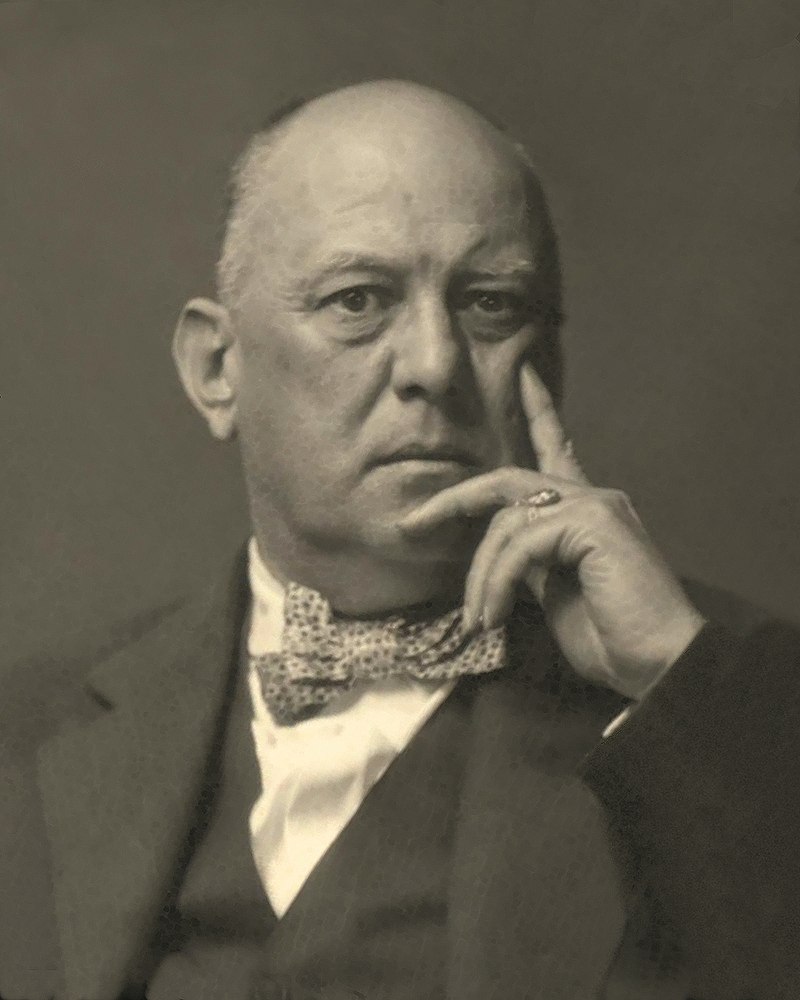

2. Aleister Crowley

Among Gardner’s influences – and one of the larger-than-life figures of the occult, generally – was Edward Alexander “Aleister” Crowley.

Born around the middle of the class-conscious Victorian Era, Crowley was initially given a strict Christian upbringing under the auspices of the Plymouth Brethren. The Brethren were an eschatologically obsessed Protestant group that included ministers, like John Nelson Darby, who had split from Anglicanism.70

For Crowley, this apocalyptic environment – combined, when he was only eleven years old, with the death of his father – seems to have galvanized him to embrace the persona of θηρίον (Thērion, the “Beast”) for – what seems in his mind to have been – an epic lifelong battle against Christianity.

He would come (no pun intended) to see this effort as being bound up with sex magic and it would involve him with numerous wives, mistresses, and other sexual partners – both female71 as well male.72

In a seminal instance of such “magick” (which word Crowley spelled with a final “k”), and revealing something of Crowley’s appreciation of Lévi, he and Victor Neuberg (a young Trinity-College graduate, poet, and student of the occult) supposedly crossed some sort of Kabbalistic “Abyss.”

According to Crowley’s (possibly embellished) account, the duo encountered a destructive “Guardian of the Threshold”73 named “Choronzon” – which entity had previously identified as a demon by John Dee and Edward Kelley.

Crowley, independently wealthy from a substantial trust fund, directed his money and time into accumulating occult knowledge. At various times he joined numerous secret societies, including the Freemasons, “MacGregor” Mathers’ Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, and Theodor Reuss’s Ordo Templi Orientis (or the “Order of the Temple of the East”), abbreviated “O.T.O.”74

He even created his own order, typically designated only by the characters “A∴A∴.” Numerous possible interpretations of this name have been put forward, with the usual (though disputed) suggestion being that it stands for Argentium Astrum, meaning “Silver Star.”75

But, Crowley expressed dissatisfaction with many of these associations – and frequently disparaged fellow members as mere poseurs.

Apparently determined to excavate genuine magical secrets for himself, he embarked on a series of reportedly dangerous rituals in dynamic locations. One such, was the allegedly black-magical Rite of Abramelin that he undertook at Boleskine House on the shore of Loch Ness in Scotland.76

Or again, in Egypt, Crowley alleged that, in 1904, while on his honeymoon with first wife Rose Kelly, he channeled a document known as The Book of the Law77 from an entity named “Aiwass,” during a ritual referred to as the “Cairo Working.”

In Crowley’s view, The Book of the Law was to serve as a foundation for a new religious and social order, built – in part – atop the maxim “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law.”

Crowley attempted to model his ideal in Cefalù, on the Island of Sicily.

He styled this Italian-based occultic commune, the “Abbey of Thelema,” after a fictional predecessor78 featured in 16th-c. humanist-monk François Rabelais’s satirical and vulgar Gargantua and Pantagruel novels published in the 1530s.

It was a fairly short-lived experiment, however, as Crowley and his devotees were expelled by Benito Mussolini in 1923 following the death of young Oxford graduate Frederick “Raoul” Loveday, whose widow later reported that her husband had taken ill after drinking animal blood during a black-magical ceremony.

Regardless of the account’s veracity, it helped to cement Crowley’s reputation as the “wickedest man in the world” – as one newspaper headline once stated.

This notoriety was only furthered by his own writings, such as the Diary of a Drug Fiend, published in 1922,79 and The Confessions of Aleister Crowley, posthumously published in a full edition in 1969.80

Crowley was an inspiration to many of the pop-cultural icons promoting the “sex, drugs, and rock&roll” atmosphere of the 1960s, including John Lennon (who was apparently instrumental in seeing that Crowley’s image was featured on the Beatles’ 8th album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band), Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page (who later acquired Boleskine House), and – for a time – the members of the Rolling Stones (who had been introduced to Crowley via Lucifer Rising director, Kenneth Anger).

Runners up…

Of course, occultism owes much to numerous others. Attempting to list all the relevant names would be an exercise in futility. Suffice it to say that, apart from other actors already mentioned in passing, other characters such as Francis Bacon, the Biblical characters like Enoch and King Solomon, alchemical figures like Nicolas Flamel and Paracelsus, Neo-Platonists Iamblichus and Plotinus, and curious personalities like Hermes Trismegistus and Anton Mesmer – whether historical or fictional – will appear in forthcoming videos. But, for now…

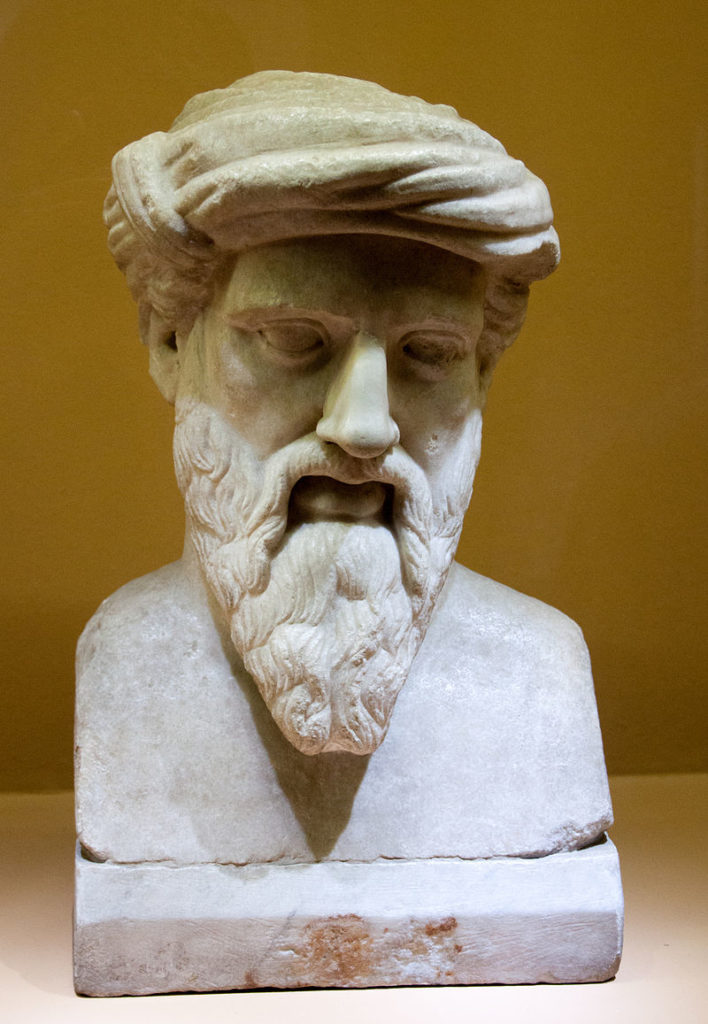

1. Pythagoras

Pythagoras was a truly pioneering Greek thinker who radically impacted the development of numerous important disciplines including cosmology, mathematics, and philosophy – which word, meaning the “love of wisdom,” he is said to have coined.

Blavatsky – true to her form – asserts that “…Pythagoras learned from the Egyptian hierophants” and “Hindu sages,” but also holds that he was the fountainhead of a philosophy that was subsequently delivered through Socrates and Plato.81

Pythagoras dramatically affected the course of subsequent Western occultism.

He was born on the Greek island of Samos in the Aegean Sea about the year 570 B.C.E. His life after that is something of a question mark.

Chroniclers say that he traveled widely and was initiated into numerous “mystery religions” and wisdom traditions.

Curious stories abound with respect to Pythagoras. He supposedly had magical powers and “a golden thigh; …he had the gift of prophecy; and he could be at different places at the same time. Like Orpheus, he had power over animals… All these characteristics indicate that Pythagoras was no ordinary human being; he was a ‘divine man,’ … or shaman…”.82

Pythagoras eventually founded his own commune in a what is now the Italian city of Crotone.

There, Pythagoras taught his students the secrets he had learned, creating an esoteric body of thought called “Pythagoreanism.”

Evidently, he did nothing to dispel the idea that he was a “miracle worker” and his awe-inspired followers submitted to an almost cult-like system of community regulations and rules – a system in which only a select group would be taught his entire philosophy.

Pythagoreanism seems to have involved numerous, original concepts.

Arguably, three of the most important were a belief in the reincarnation of souls, commitment to the notion that the visible world of objects issued or “emanated” from some ultimate metaphysical reality, and an assertion of the fundamental existence – and magical power – of numbers.

These ideas dovetailed in interesting ways, prompting Pythagoras have discovered noteworthy geometrical and numerical relationships, such as that between the hypotenuse and sides of a right triangle – an insight still conveyed to school children as the Pythagorean Theorem, and given towering mystical and symbolical proportions in Freemasonry.

Beyond contributions to abstract thinking, some observers look to Pythagoras as a precursor to modern science. For instance, he taught that the universe was a rationally ordered cosmos that could be understood mathematically.

But Pythagoreanism also helped shape such occult traditions as alchemy, Gnosticism, Neo-Platonism, Paracelsianism, Rosicrucianism and, much later, the Theosophy and the New-Age Movement.

Aleister Crowley even wrote that “…the Qabalists who invented the Tree of Life were [probably] inspired by Pythagoras, or that both he and they derived their knowledge from a common source in higher antiquity.”83

This link between Kabbalism – and Merkavah mysticism – and Pythagoras is also asserted by Lévi (as translated by Waite), who adds the flourish that this ancient sage is also connected to the mysterious number “666” mentioned in Revelation 13:18.84

Finally, would you believe that the Pythagoreans may also have anticipated modern-day Vegans and others by embracing some sort of ancient vegetarianism? Some sources suggest that this was actually the case – either that or Pythagoras at least seems to have adopted and required his followers to observe dietary restrictions, not unlike those associated with Judaism (though, for different reasons).

With such a remarkable impact, it’s no wonder present-day Masons refer to Pythagoras as their “ancient friend and Brother.”

To paraphrase the wander maker, Ollivander, in J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter franchise: Some of these esoterics and occultists “…did great things. Terrible? Yes. But… great!”

In your opinion, did I miss anyone? Who would you have added or removed? What’s your own top-10 list?

There are plenty more figures that I could have been included. I intend to remedy some deficits with future lists.

Hope to see you next time!

Notes:

1See Douglas Harper, “Occult,” Online Etymology Dictionary, n.d., <https://www.etymonline.com/word/occult>.

2See, e.g., Stephen Klimczuk and Gerald Warner, Secret Places, Hidden Sanctuaries: Uncovering Mysterious Sites, Symbols, and Societies, London & New York: Sterling Ethos, 2009, pp. 81ff.

3According to the celebrated 18th-19th-c. German playwright Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Cagliostro may actually have been Jewish. If true, this would provide some context for his reputed knowledge of Hebrew tradition. Goethe, Italian Journey, 1786-1788, London: Penguin, 1970, p. 249; online at: <https://books.google.com/books?id=ioXNoJa6qNsC&pg=PA249>.

4See Jim Brandon, “Sirius Rising,” audio recording, ca. 1970s.

5Charles Shyer, The Affair of the Necklace.

6Some of the Western exposure to Eastern/Greek ideas came via the Council of Florence (convoked to discuss the debate between Conciliarists and Papalists and the Great Schism), which was attended by hundreds of delegates, including “Plethon” (Gemistus Pletho). Plethon was noteworthy because he rejected Christianity in favor or a Neo-Platonically tinged version of paganism that was also reportedly a blend of angelology, astrology, and mysticism, seasoned with elements of Stoicism (presumably, some sort of asceticism) as well as Zoroastrianism. This combinatorial exercise will be echoed and repeated by many of the figures appearing on this list.

7This framework had been devised by the Hellenistic philosopher Plotinus and his more magically inclined succssor, Iamblichus.

8Together, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew were sometimes designated the “Three Languages.”

9Frances Yates, The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age, London: Routledge, 1999, p. 97.

10First under King Henry VIII and Henry’s, son Edward VI (and John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, acting as regent), and then under Queens Mary and Elizabeth I.

11Believe it or not, this was once a respectable position, and it was held by numerous individuals such as famed astronomer Tycho Brahe (for Danish King Frederick II); Hermeticist Giordano Bruno (e.g., for the House of Mocenigo, which ultimately produced Bruno’s accuser, Giovanni Zuane Mocenigo); mathematician Gerolamo Cardano (for English King Edward VI); formulator of the “laws of planetary motion,” Johannes Kepler (for Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II); alleged French seer Nostradamus (for Florentine noblewoman and Queen Consort to French King Henry II, Catherine de Medici); and even scientific hero Galileo (for Tuscan Duke Cosimo II de’Medici).

12Today, Dee’s journal is known as De Heptarchia Mystica (or, “On the Mystical Rule of the Seven Planets,” ca. 1582).

13Since, obsidian is a black, volanic stone, it’s interesting (to this writer) that Charlie Brooker’s Netflix-original show has the title Black Mirror.

14A.k.a., the Aldaraia.

15See <https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Fourth_Book_of_Occult_Philosophy>.

16Liber Juratus Honorii.

17In what was once metaphorically referred to by 20th -c. mystic and psychedelic advocate Terence McKenna as an occultic analog to the 1st -c. Christian-missionary journeys undertaken by St. Paul. See Terence McKenna, The Alchemical Dream: Rebirth of the Great Work, Sheldon Rochlin, ed., DVD, Sacred Mysteries Productions; Mystic Fire Productions; 2008.

18Including the “fruit portraiture” of Giuseppe Acrimboldo.

19Ostensibly in an effort to unlock the secrets of the “Philosopher’s Stone” and perhaps to create gold.

20Which had been a respectable European pursuit at least since Ptolemy’s pioneering Tetrabiblos. Though, undoubtedly, the notions go back to Egypt – if not earlier.

21Born Michel de Nostradame.

22This proto-chemist was supposed to have unlocked the transmutation of lead into gold.

23Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel, a.k.a., the “Maharal.”

24Richard Deacon, John Dee: Scientist, Geographer, Astrologer and Secret Agent to Elizabeth I, London, Muller, 1968, pp. 5 et passim.

25Weird Tales, Apr., 1929, pp. 481–508; available online at: <https://www.hplovecraft.com/writings/texts/fiction/dh.aspx>.

26Partly based on Dee’s Liber Loagaeth.

27Russell Adams, Jr., et al., eds., Mysteries of the Unknown: Ancient Wisdom and Secret Sects, Alexandria, Virg.: Time-Life Books, 1989, p. 153.

28It has even been alleged that Pike had something to do with – or, perhaps, held membership or leadership in – the infamous Ku Klux Klan. However, evidence for this appears scant and in in any case, the Klan is more typically associated with Pike’s Confederate colleague, Nathan Bedford Forrest, who indisputably served as the organization’s first “Grand Wizard.”

29Recent attempts have been made to rehabilitate Pike’s image vis-à-vis his “racism.” One such effort appears under the headline “Albert Pike did not found the Ku Klux Klan,” and was published on the website of the Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon (Nov. 26, 2012, <https://freemasonry.bcy.ca/anti-masonry/kkk.html>). The reference is prominent enough to receive a citation in Pike’s entry (“Albert Pike,” Sept. 9, 2021, <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_Pike>) for the popular internet-based encyclopedia Wikipedia.

In both resources (op. cit.), Pike is excerpted (see full citation for the original source, infra.) to the following effect: “I am not one of those who believe slavery a blessing. I know it is an evil, as great cities are an evil…”. Pike proceeds to compare the evil of slavery to evils of wage labor and military service – presumably because both of which, like slavery, undermine “free-will and individuality”.

However, this opinion did not stop Pike from participating in the institution of slavery. He also wrote, in the sentence preceeding the widely quoted statement (no less): “I have owned only such slaves as I needed for household servants.” (Fred William Allsopp, Albert Pike: A Biography, Little Rock, Ark.: Parke-Harper, 1928, p. 181.)

Thus, even the freemasonic website admits that Pike’s “racism …[is]nothing to be proud of”. (“Albert Pike did not found the Ku Klux Klan,” loc. cit.).

30Robert Lipscomb Duncan, Reluctant General: The Life and Times of Albert Pike, N.Y.: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1961, p. 155.

31Christian Pinto, “Eye of the Phoenix: Secrets of the Dollar Bill,” Secret Mysteries of America’s Beginnings: Volume 3, DVD, N.p.: Antiquities Research Films, 2009.

32Whose origin surname was supposedly “von Hahn.”

33Along with Americans Colonel Henry Steel Olcott and William Judge.

34This conjunction of East and West was part of the Zeitgeist, apparently, as one of the first “interfaith” conventions – called the “World’s Parliament of Religions” – convened, under the auspices of Chicago’s Columbian Exposition, on September 11, 1893.

35London: Theosophical Publ. House,; New York: J.W. Bouton,1877;

36Blavatsky was accused of plagiarism, particularly by William Emmette Coleman. Coleman was a 19th-c. academic specializing in studies of the Far East and the Near East, then referred to as “Orientalism.” He was also an avid spiritualist, himself. So, prima facie, his criticisms do not seem to have been ideologically motivated. See William Emmette Coleman, “ The Sources of Madame Blavatsky’s Writings,” Vsevolod Sergyeevich Solovyoff, A Modern Priestess of Isis, London: Longmans, Green, & Co., 1895, Appendix C, pp. 353-366; reproduced online at: Blavatsky Study Center, 2004, <https://www.blavatskyarchives.com/colemansources1895.htm>.

37Incidentally, Hermetic-Order-of-the-Golden-Dawn head honcho, Samuel Liddell “MacGregor” Mathers, also maintained that he was in contact with a coterie of “Secret Chiefs” who helped him steer his organization and draft its rituals.

38Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, Helena Blavatsky, Berkeley, Cal.: North Atlantic Books, 2004, p. 17.

39Ibid., pp. 17-18.

40Ibid.

41See George Lachman, Madame Blavatsky, New York: Penguin, 2012, pp. 254-255.

42“A Case Study: Reincarnation,” Claiming Knowledge: Strategies of Epistemology from Theosophy to the New Age, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2004, p. 455; available online at: <https://brill.com/view/book/9789047403371/BP000008.xml>.

43Whether this story is true or not, I cannot say. But it is accepted – if only prima facie – by some scholars. See, e.g., Bengt Ankarloo, Stuart Clark, eds., Witchcraft and Magic in Europe: The Twentieth Century, Philadelphia: Univ. of Penn. Press, 1999, p. 96 & Susan Greenwood, The Encyclopedia of Magic & Witchcraft, London: Hermes, 2004, p. 239.

44Paramount, 1968.

45New York: Avon Books.

46New York: Dodd, Mead, & Co.; Lancer Books.

47Los Angeles: Feral House, 1989.

48New York: Avon Books.

49See “Information for Prison Chaplains,” Church of Satan [website], n.d., <https://www.churchofsatan.com/info-for-chaplains/>.

50Peter Gilmore, “Satanism: The Feared Religion,” Church of Satan [website], n.d. [orig. 1992], <https://www.churchofsatan.com/satanism-the-feared-religion/>.

51The phrase owes to Nietzsche (see his aphorism “This world is the Will to Power—and nothing else!” in paragraph 1067 of his Nachlass, loc. cit., infra.), even though the title of the posthumously published Der Wille zur Macht (Leipzig: Naumann, 1901) was the brainchild of his sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche.

52Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung (“The World as Will and Representation”), Leipzig: Brodhaus, 1819.

53As articulated, for instance, in her novels The Fountainhead (Indianapolis, Ind.: Bobbs Merrill, 1943) and Atlas Shrugged (New York: Random House, 1957).

54The beginnings of which are found in Liber AL vel Legis (“The Book of the Law”) which Crowley attributed to a spirit or demon called “Aiwass” and which Crowley privately published in 1909. For a bit more, see the section on Crowley, below.

55See his encyclical Mirari vos (on liberalism and religious indifferentism, 1832).

56See Quanta cura (“Condemning Current Errors,” 1864).

57Alphonse-Louis Constant, Paris: Le Gallois, 1841.

58For example, according to him: “Imagination …is like the soul’s eye; …it is the glass of visions and the apparatus of magical life… [I]t is the imagination which exalts the will…”. Transcendental Magic: Its Doctrine and Ritual [orig. Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie], Arthur Edward Waite, ed., transl., Chicago: Occult Publ. House, 1910, pp. 34-35; online at: <https://books.google.com/books?id=XI_kwB0uW10C&pg=PA34>.

59London: Lackington, Allen & Co., 1801 .

60Mysteries of the Unknown: Ancient Wisdom and Secret Sects, Arlington, Virg.: Time-Life, 1989, p. 66.

61Leslie George Mitchell, Bulwer-Lytton: The Rise and Fall of a Victorian Man of Letters, London: Hambledon and London, 2003, p. 142.

62London: John Dicks. More interestingly, the French magus may even have inspired – or informed – Bulwer-Lytton’s The Haunted and the Haunters (N.p.: n.p., 1857 / 1859) and A Strange Story (London: S. Low, Son & Co., 1862), at least, according to uncited information on an occultically themed website. See “Levi, Eliphas,” ca. 2003, <https://occult-world.com/levi-eliphas/>. Incidentally, the publication particulars are a bit difficult to discover through the usual channels (e.g., via WorldCat). It seems that the two publications are sometimes packaged together. E.g., see: A Strange Story And The Haunted & the Haunters (London: G. Routledge and Sons, 1866); available online at: <https://books.google.com/books?id=JHIRAAAAYAAJ>.

63London: D. Nutt, 1899.

64London: Kegan Paul, 1891.

65Oxford: Clarendon, 1921.

66Scire (Gerald Brosseau Gardner), High Magic’s Aid, London: Michael Houghton, 1949.

67London: Rider, 1954. Of course, Rider was the company that published Arthur Edward Waite’s famous Tarot-card deck – now known as the Rider-Waite Tarot.

68London: Aquarian Press, 1959.

69See, e.g., N.a., “Wicca: What’s the Fascination?” CBN, n.d., <https://www1.cbn.com/books/wicca%3A-what%27s-the-fascination%3F>; “It’s a moot point, but Paganism may be the fastest growing religion in Britain,” Yorkshire Post, Oct. 31, 2013, <https://www.yorkshirepost.co.uk/news/its-moot-point-paganism-may-be-fastest-growing-religion-britain-1853590>; and Mary Jones, “’Wicca’: The Fastest Growing Belief System in the World Today,” Press Release Log, Nov. 20, 2008, <https://www.prlog.org/10144283-wicca-the-fastest-growing-belief-system-in-the-world-today.html>. Though, admittedly, other sources claim that Islam is growing quicker. Cf. “Islam: The World’s Fast-Growing Religion,” BBC, Mar. 16, 2017, <https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-39279631>.

70Darby is an interesting character in his own right, since he – arguably more than any other person – is responsible for the popularity of so-called “Premillennial Dispensationalism,” an interpretation of the Biblical books of Daniel and Revelation maintaining that much of the apocalyptic and prophetic language describes an “end-times” reign of the “Anti-Christ.” This story line was further developed by Hal Lindsey in his 1970 best seller, The Late, Great Planet Earth, (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan.) and made into a movie based on the Left Behind series of novels written by Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins (Carol Stream, Ill.: Tyndale House Publ., 1995.).

71Such as Leah Hirsig and Leila Waddell. Crowley apparently referred to these sexual partners as “Scarlet Women,” and thought they were incarnations of the Biblical “Whore of Babylon,” which he designated with the variant spelling, Babalon.

72E.g., Victor Neuburg. See, e.g., James Webb, The Occult Establishment, La Salle, Ill.: Open Court, 1991, p. 61.

73Also called the “Dweller on the Threshold,” which concept owes to the previously name Baron Bulwer-Lytton. See his Zanoni, London: G. Routledge, 1842.

74Just as Mathers is named along with co-founders William Wynn Westcott and William Robert Woodman, so too is Reuss also associated with two others: Carl Kellner and Franz Hartmann.

75Other suggestions include Arcanum Arcanorum (“Secret of Secrets”) and Argon Astron (“Silver Star” in Greek – alternatively, Asimēnio Astēri).

76According to S.L. “MacGregor” Mathers, citing his friend and fellow occultist Henri Antoine Jules-Bois; see The Book of the Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage, Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Occult, 1975, p. xvi.

77Liber AL vel Legis.

78The Abbaye de Thélème.

79London: Collins.

80London: Cape.

81H. P. Blavatsky, Isis Unveiled, Vol. 1, Wheaton, Ill.: Quest Books, 1994, pp. 7, xx, and xvii.

82According to Georg Luck, Arcana Mundi: Magic and the Occult in the Greek and Roman Worlds: A Collection of Ancient Texts, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 2006, p. 42.

83Aleister Crowley, Book of Thoth, reprint ed., Boston: Weiser Books, 2004 [1944], p. 31.

84See Éliphas Lévi, transl., Arthur Edward Waite, Transcendental Magic: Its Doctrine and Ritual, New York: E.P. Dutton, 1938, p. 211.